Leonard Cohen, and thoughts related to the Yom Kippur war of 1973

Wednesday, October 11, 2023

(In mid September, 2022, I began a series commemorating the 50th anniversary of my coming-of-age trek across Europe and Israel in 1972. I posted eleven episodes before being interrupted at Thanksgiving time. This would probably come in at something like episode twenty, but I'm putting it here for other reasons which should become obvious. Technical difficulties prevented me from posting this when I first wrote it, on September 24, which was the 50th Yom Kippur since the 1973 war. It was also before the outbreak of the war now being fought.)

At a couple of minutes before 2:00, on the afternoon of Yom Kippur (October 6, in 1973, but ending at sundown this evening, September 25, 50 years later), when a coalition with troops from twelve nations launched a surprise attack upon Israel, many Jews both in Israel and elsewhere around the world were at synagogue services, observing their Day of Atonement, the most holy fast of the year. Canadian singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen, in line by birth to the Levitical priesthood, was on the Greek island of Hydra, just off the Peloponnesian coast, with a woman named Suzanne (but not the Suzanne from his song of that name) and their toddler. He was 39 and feared he was washed up as a performer. He had never served in the military, even for his native Canada, and had the reputation of being something of a pacifist. Although he had lapsed as an observant Jew, at hearing the news of war, he took the ferry to the mainland, traveling light. He did not even take his guitar.

I, a gentile, was settling into my first year of marriage. We had spent our first six weeks at a family cabin at Mt. Baldy Village, just outside Los Angeles, and now we were back in the city. I had seen Cohen in concert at UCLA, three years earlier, from a second-row seat in the very center, smack dab in front of him. While attendees were arriving to fill Royce Hall, a voice in the back began to rant wildly and Cohen came from behind the curtain. The heckler came forward and the two sat on the edge of the stage and talked quietly. Cohen settled him down and gave him a parting hug. I did not know it, but just a couple of months earlier, while touring Europe, Cohen had talked his backup musicians into a concert at a mental hospital. When a patient stood mid-concert and challenged Cohen with a question about what the singer would do for him, Cohen set aside his guitar, went into the audience, and held the man in an embrace.

Only as I researched this essay did I learn that the interrupter in Royce had been actor Dennis Hopper, a friend of Cohen’s. For a period of eight days, right then, Hopper had been married to Michelle Phillips, recently divorced from both John Phillips and the Mammas and the Papas. She would be singing backup in the second half of the show, and Hopper had talked Cohen into giving her the job. For the first half of the concert, Cohen shared the stage only with a chair, a microphone, and his guitar. He sang songs that I knew well from his two albums, most notably, “Suzanne,’ “Sisters of Mercy,” “So Long, Marianne,” and “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye.” Cohen’s genius was for quiet lullabies of detachment and desperation. Cohen had difficulty forming attachments, but he had a talent for turning goodbyes into great poetry and hypnotic music.

I'm not looking for another as I wander in my time

Walk me to the corner, our steps will always rhyme

You know my love goes with you as your love stays with me

It's just the way it changes, like the shoreline and the sea

But let's not talk of love or chains and things we can't untie

Your eyes are soft with sorrow

Hey, that's no way to say goodbye

His goodbye to Suzanne (not that Suzanne) on Hydra was more of a ‘I’m not sure what I’m doing, but I know I have to go, and I may be back.’ He got on the ferry, and then an airplane, and arrived at Lod Airport in Tel Aviv.

Eleven months previous, I too landed at Lod, with even less reason to be there. After graduating from UCLA, I bought a one-way ticket to London, thinking I would get as far as France to spend a year. Then, before I could actually use that ticket, I fell hard for the only woman I have ever loved, and to whom I am married today. Cohen and I are opposites in so many ways, yet his songs have fascinated me now for some 55 years.

I knew I was coming back Stateside in just a few months. However, while hitch-hiking through Europe, doors opened and doors closed, rides either materialized or didn’t, and instead of Paris, I visited Amsterdam, Berlin, Basel, Venice, Belgrade, and Istanbul. First in East Germany and then in the West, I encountered God in a way I could never go back upon, and in ways I don’t believe Cohen ever did. When doors opened to direct me to Israel, I was ready for it. I arrived at Lod airport on an El Al flight from Istanbul. At both ends of the flight, passengers faced the strictest security I have ever seen, even after 9/11. In that November, 1972, only six months had passed since members of the Japanese Red Army pulled machine guns from their luggage, killing 26 and injuring 80.

Cohen had been to Jerusalem in April, at the end of his 1972 European tour. Once on stage, he’d become flustered when the crowd applauded after the first few words of “Like a Bird on a Wire.”

Like a bird on the wire,

like a drunk in a midnight choir

I have tried in my way to be free.

He stopped singing and explained why he could not go on with the concert, “…it says in the Kabbalah that unless Adam and Eve face each other, God does not sit on his throne. And somehow, the male and female part of me refuse to encounter one another tonight, and God does not sit on his throne. And this is a terrible thing to happen in Jerusalem.” (https://www.israellycool.com/.../when-leonard-cohen.../) Cohen then walked off, followed by the band. At that point, the audience took up spontaneous versions of well-known songs in Hebrew. Back stage, Cohen shaved while the promoters and band tried to coax him back on stage. In his guitar case, he found an old package of LSD, which he split up among them, later describing the shared acid as “like the Eucharist.” It was Cohen’s special talent to use sacred imagery to describe the profane. After this ‘priestly’ duty, Cohen returned to the stage, crying, to listen to the crowd sing, and add a song of his own.

In Jerusalem, I located an acquaintance from UCLA, named Ilene. The next day, she snuck me onto a field trip with her Palestinian Archeology class. In the role of academics, we hopscotched north along the Jordan River, to stops in Galilee and catacombs near Haifa, listening to lectures. Then Ilene and I hitchhiked for a weekend in Safed, an artist’s colony and the highest city in Israel. Under the Ottoman rulers, Safed had been the study-center of Kabbalah. Alongside Israeli soldiers, we waited for rides at hitching points. The soldiers then put in a good word for us with any drivers who stopped. We rode along the border of the Golan Heights, chatting with our armed escorts. In Safed, we watched a continuous pattern of Israeli Air Force planes patrolling the Lebanese border, only about ten miles away.

In Tel Aviv, Cohen thought he would volunteer for work on a kibbutz, but visited cafés that he remembered from the disastrous tour of 20 months earlier. There, musicians recognized him and invited him to help entertain troops in the Sinai Desert, where the war was going very badly. They found him a guitar.

Actually, the war was going badly everywhere. The simultaneous attacks from Egypt into the Sinai and from Syria into the Golan Heights had caught an overconfident and relaxed Israel during a holiday. Observant Jews were between the first and second of the three main portions of the liturgy, and non-observant Jews were indulging themselves in secular pleasures.

Cohen would have been in this second group. Although raised in a Montreal synagogue founded by his rabbi grandfather, and deeply infused by its rhythms and language, Leonard Cohen was faith-curious, but living the life of a secular man. Israeli journalist Matti Friedman, author of WHO BY FIRE: LEONARD COHEN IN THE SINAI, describes Cohen’s public image as “a poet of cigarettes and sex and quiet human desperation, who’d dismissed the Jewish community that raised him as a vessel of empty ritual, who despised violence and thought little of states…” (p. 5). Yet much later, when Cohen was residing at a Zen Buddhist monastery, just two miles upstream from my family’s cabin at Mt. Baldy, he would tell an interviewer, “…I was never looking for a new religion. I have a very good religion, which is called Judaism. I have no interest in acquiring another religion.” (p. 41)

It intrigues me that Cohen, and an impressive list of other secular Jews, including Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Randy Newman, and Carly Simon, provided my generation with its musical score and lyrics, the Psalms of our secular experience.

Cohen knew well that he had been born in the bloodline of priests—Kohanim in Hebrew—running through his grandfather, then through 3,000 years of fathers and sons to the generation of Zadok, chief priest at the time of Solomon’s Temple. Finally it sound its Levitical source in Aaron, the brother of Moses. Cohen struggled with that. A new acquaintance in Tel Aviv sized him up quickly, “You must decide whether you are a lecher or a priest.” (p. 166). In notes he assembled just after the war, perhaps for a novel he never produced, Cohen recounts, “The interior voice said, you will only sing again if you give up lechery. Choose.” (p. 48). In the Temple, one whole branch of the priests were singers. Cohen was at a point in life where he doubted even that hereditary gift.

What Cohen could not have known, at least until he was living at the Zen Monastery, was that DNA studies in the late 1990s concluded that the genetic code bore out the historicity of this Kohanim tradition. Researchers have identified a pattern of genetic markers that is as much as ten times more common among Cohens than for non-Kohanim-Jews. That holds true among both Ashkenazi and Sephardic populations, and even for Lemba tribesmen in Zimbabwe and South Africa, who maintain a tradition of Jewishness.

Out in the Sinai Desert, at one end of the father-to-son chain of Kohanim, Moses recorded God’s declaration that only men from this one family could service the Tabernacle. Among their duties would be calling the people away from their daily tasks, often ministering during the worship with singing and musical instruments. Now, at the other end of the chain, Leonard Cohen, much though he might want to escape the priesthood, was heading into the Sinai to minister in music to the troops.

The Sinai was bathed in blood. The small troop of musicians would drive until they saw a cluster of soldiers, stop, and sing a few songs. Sometimes these soldiers were just arriving from hot battle, with minutes-old images of flying ordinance and falling comrades. Many were not sure who this singer was, nor could they understand the English of the songs he sang. He spoke no Hebrew. Few understood that here was a musician who had sung in 1970 before for a crowd of 600,000 on the Isle of Wight. Most were more excited to see the Israeli singers that they recognized. Cohen sang standing in a tight circle of soldiers, or sitting in the sand, or on the scoop of a bulldozer. One photograph shows him standing in front of General Ariel Sharon, who is talking to a well-known Israeli singer. Later, Sharon did not remember that Cohen had been there. (p. 141)

counter-offensive across the Suez into Egypt. At one point, Cohen helped carry stretchers with wounded soldiers from helicopters to a makeshift hospital. His memoire records that as they moved through territory that had seen recent battle, he recoiled against the sight of bodies littering the sand, but felt relief when he learned the dead were Egyptians, not Jews. Then he felt guilt for feeling that relief. Those had been some mothers’ sons. There was no LSD to cushion what he was seeing, only soldiers’ rations and quick naps on the sand. In between performances he worked out a new song, though the recorded version is gentler in places than the verses he sang in the desert.

I asked my father

I said, father change my name

The one I'm using now it's covered up

With fear and filth and cowardice and shame…

He said, I locked you in this body

I meant it as a kind of trial

You can use it for a weapon

Or to make some woman smile...

Yes and lover, lover, lover, lover, lover,

lover, lover come back to me

Yes and lover, lover, lover, lover, lover,

lover, lover come back to me

Then let me start again, I cried

I want a face that's fair this time

I want a spirit that is calm…

Yes and lover, lover, lover, lover, lover,

lover, lover come back to me

Yes and lover, lover, lover, lover, lover,

lover, lover come back to me

Of the three liturgical high points of the Yom Kippur commemoration—due to its solemnity, not to be confused with a celebration—the first, a thousand-year-old prayer called Unetaneh Tokef, had been recited before the coordinated attacks. It begins, “Let us relate the power of this day’s holiness.” It speaks of God’s judgements, the insignificance of man, and projects the idea that this Day of Atonement seals everyone’s fate for the coming year:

How many will pass on and how many be created,

Who will live and who will die,

Who will reach the end of their days and who will not,

Who by wind and who by fire,

Who by the sword and who by wild beast,

Who by famine and who by thirst… (p. 16)

This prayer formed the inspiration for Cohen’s 1974 song, ‘Who by Fire.’

During the second high point, all the male Cohens in the congregation stand around the gathering to recite a blessing that was left as a vestige after the destruction of the Second Temple, by the Romans, in 70 AD. “May God bless you and guard you. May God shine His face upon you and be gracious to you. May God lift up His face to you and grant you peace.” (p. 17)

The third and final highpoint, reached at the very end of the 24-hour fast, when everyone is tired, is a reading of the Book of Jonah, the most complex history ever presented in 48 sentences. At the beginning of 2022, on my short list of New Year’s resolutions, I wrote that I wanted to better understand Jonah. Eighteen months later, I think I am finally getting it, although perhaps I’m not taking the same message that all Yom Kippur worshippers are receiving.

Jonah, a prophet of God, is told to take a message to the people of Nineveh, not only pagans, but as wicked and blood-thirsty a city as ever existed. Jonah hops a boat going the opposite direction. He knows that he cannot escape from God, but perhaps he can escape from his job description. In a storm, he finds himself in the hands of pagans more righteous than he, but God uses him to demonstrate to those pagans His own awesome power. Then Jonah is swallowed by a fish, and surrenders himself to God’s will. The fish spits him up on the shore, and Jonah goes to preach in Nineveh. I have seen speculation that after three days stewing in a fish’s stomach juices, Jonah may have arrived in Nineveh looking like God’s demonstration project. The Ninevites repent, and God spares them from the judgement that He had pronounced. Jonah goes to sulk on a hilltop, where God provides a vine for shade and then a worm to kill the vine. Jonah is angry at God, both for His mercy on the wicked Ninevites and for taking away the protective shade, and God challenges him that he has no right or reason to stand in judgement on the Creator.

Why should Jonah’s memoire be read as the culminating activity on the Day of Atonement? In a very real sense, Jonah is Everyman, and we are all in need of atonement. We have all, together, and each, individually attempted to run from God and the job descriptions He has given us. We have all and each of us attempted to cast judgement on God for both the unrighteous who He has blessed and the righteous He has apparently overlooked. Even honest atheists, if they examine their hearts, will likely discover that their disbelief in God is rooted in those judgements.

But for Israel—and ratchet it up a notch for the Cohens—the job description is even more direct. Beginning with Abraham, God’s chosen people, like Jonah, were chosen to be God’s demonstration project. In this allegory, the rest of us are Ninevites.

The temptation for the chosen is to run as Jonah did, or to pass the job description off on others. Fiddler on the Roof’s Tevye, addressing God, says, “I know, I know. We are Your chosen people. But, once in a while, can't You choose someone else?”

God very clearly sets out the stakes in this demonstration. By the time we get to Deuteronomy, chapters 27-30, Moses has completed his 40 years leading the Hebrews around in the Sinai. He gives his final instructions—rules against theft, mistreatment of the vulnerable, and lechery. Then, before turning them over to Joshua’s leadership and sending them across the Jordan, Moses tells the leaders that once they are in Israel, they are to put half the people on Mount Gerizim. There, they will shout a list of blessings that will come from obedience to God. Facing them, the other half will stand on nearby Mount Ebal, to shout curses that will follow disobedience. The script acknowledges that it’s for demonstration purposes. Concerning the blessings: “Then all the peoples on earth will see that you are called by the name of the LORD… “ (28:10a) Then later, concerning the curses: “The LORD will cause you to be defeated before your enemies. You will come at them from one direction but flee from them in seven, and you will become a thing of horror to all the kingdoms on earth.” (28:25). And again: “You will become a thing of horror, a byword and an object of ridicule among all the peoples where the LORD will drive you.” (28:37)

The curses require a long chapter, remarkably foretelling the actual experience of the Jewish Diaspora: “Then the LORD will scatter you among all nations, from one end of the earth to the other…” (28:64) “Among those nations you will find no repose, no resting place for the sole of your foot. There the LORD will give you an anxious mind, eyes weary with longing, and a despairing heart. You will live in constant suspense, filled with dread both night and day, never sure of your life.” (28:65-66)

However, Chapter 30 speaks of a restoration. Many of the families that were taken away to Babylon in the exile never got back to Israel. Cohen’s ancestors became Polish and Lithuanian Ashkenazim. Other families became the Sephardic population of Iberia. Yet over the course of 2,500 years they never lost their identity or the pull of the land. “Then the LORD your God will restore your fortunes and have compassion on you and gather you again from all the nations where he scattered you. Even if you have been banished to the most distant land under the heavens, from there the LORD your God will gather you and bring you back.” (30:3-4)

That pull was so strong, that when a secular and lecherous Canadian Cohen, while fleeing his priestly calling, heard that Israel was under attack, his response was, “I’m not sure what I’m doing, but I know I have to go, and I may be back.”

Labels: 1972, Bible, Books, Christian Worldview, Famous People, History, Israel, Memoir, Milestones, Travel, UCLA, Yom Kippur

Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #9

Saturday, October 29, 2022

Once I left Limerick and turned myself in the direction of London, I felt the tug of possible mail waiting for me in Earl’s Court. All of Ireland is only one fifth the size of California, and the trip from Limerick to Dublin is about the same as a trip from Los Angeles to San Diego, though the highway in 1972 was just one lane each direction.

From the portion that I walked, my strongest memory is the carefully designed and manicured garden on front of one house. I stood for a short time to admire it, and I’m sure my neighbors ever since have wished I had learned more from the study.

The ride I remember was with an older gentleman in a truck. We rode together long enough to pass several cemeteries, and each time, he crossed himself without interrupting our conversation. This gesture had not been part of my Methodist upbringing, and I wondered now—without saying anything—whether this was an Irish show of respect for the dead, or a more general Catholic practice.

My Irish ancestors had been Catholics, although only nominally-so within living memory. In Seattle, on the very day that the lockdown lifted at the end of the Spanish Flu, my grandmother’s sister and her beau beckoned a justice of the peace to the house for a wedding, while my grandparents waited a few days to have a wedding mass. Neither marriage lasted, though, and while I was growing up, I never knew my grandmother to practice anything I could identify as Catholic. My dad, upon enlisting in the navy, faced paperwork that asked whether he was Catholic, Protestant, or Jewish. The question stumped him. He checked the middle box, while not identifying with any of them. He attended Protestant services at sea.

Vicki’s family had also been nominally Catholic, until in her early teens she asked her father to begin taking her to mass. Then, just a few months before she met me, she became fascinated by the faith she saw in a couple of Evangelical friends at UCLA. They helped her to a ‘born again’ step of faith. When we first met, she was on fire for Jesus, and many of our early conversations were Christo-centric. Indeed, at Easter, after we had known each other about six months, I took her to the beach for a day—her favorite spot—and we sat under the jets taking off from LAX. I came away from that day with a dim view of the relationship potential between an agnostic like me, and a ‘religious fanatic,’ as I then perceived her. My parting words, as I took her home, were “Vicki, I think you will make someone a wonderful wife, but it won’t be me.” To my surprise, I had said just the right thing. At the time, she was trying to slow down two other fellows who wanted to marry her, and she wouldn’t have to worry about me. Over the next fifteen months, we each had other romantic interests, and Vicki and I could just be good friends, under no pressure.

I arrived in Dublin, but didn’t see much of the city. I bought my ferry ticket for a sleeper to Holyhead and stayed close to the terminal. I do have a favorite picture of Dublin, though. It is of my mother, from a much later trip. I trace some of my love of travel to Mom, who never got much of a chance to do so. My dad saw a lot of Asian ports while in the navy. My mother had wanted to join the WACS, but had been talked out of it. Then she had looked into going to Europe after the war to help clean up and rebuild. But again, it didn’t fit the limited vision of people whose opinion she trusted. To them, it wasn’t appropriate for a single woman. Occasionally during my growing years, however, she would reminisce over those dreams, and so there was an element of her yearnings in my travel. Some twenty years after my trip, she and my dad did get to Ireland for two weeks, and they visited us once during our years in Colombia. Most of my mother’s travel, however, was vicariously through other people's travels, or through a retirement spent teaching English to immigrants. If she couldn’t go to them, she would make the most of them coming to her.

The crossing to Holyhead was uneventful, and the boat put me back in Wales just at daybreak. It would be the longest day of my trip.Labels: 1972, Europe, Garden, Immigration, Ireland, Memoir, Travel, UCLA

Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #4

Thursday, September 29, 2022

After two days of walking the streets of London, I was ready to leave for Ireland. I figured I could do a quick loop, take a look around, return to Earl’s Court to pick up any mail, and then proceed to France to settle in. The London Underground rises above ground after it gets outside the central city, and took less than two hours to reach Oxford. I have a friend who is spending a week in Oxford at the moment, and I’m sure it will be productive time, but my goal was to reach Stratford-upon-Avon by nightfall. My one memory of Oxford is a wide grassy stretch beside the highway as I walked.

I realize that Oxford has one of the world’s fine universities, the oldest in the English-speaking world. (My youngest son would study his junior year abroad there). Oxford got its big boost in AD 1167, when my ancestor, Henry II, banned his subjects from attending the University of Paris. Of course Oxford had turned up often in biographies. Growing up in the Methodist Church, I knew about the ‘Holy Club,’ founded by Charles Wesley, led by his brother John, and including America’s first great evangelist, George Whitefield. Yet, by my late teens, I had left behind my Methodist upbringing, and could no longer claim the Wesleys as my own. Perhaps, as well, I was still burned out after my last year at UCLA. I had no strong desire to walk around another university.

I doubt that I walked the whole 39 miles from Oxford to Stratford, but I don’t recall hitching any rides. The town of Woodstock stands out, a medieval settlement that has guarded its historic appearance. I did not realize how close I was passing to Blenheim Palace—just a hundred yards off the highway—where Winston Churchill was born and where Queen Mary locked her half sister Elizabeth away. When I visited England in 2019, my main objective was time with kids and grandkids, but Blenheim was the next thing on the list of things I didn’t get to.

In Stratford, I found the Youth Hostel and checked in. Across Europe, I was to discover that the rural YHs were more attractive and less expensive than the city versions. They were mostly stately mansions that had been donated when a younger generation could not afford to pay the inheritance taxes. I seem to recall that a bed with mattress at most of the rural Hostels cost me about the equivalent of 80 cents U.S., and I was carrying my own sleeping bag. The bedrooms would have three or four sets of bunkbeds, and guests could use the kitchen, though no meals were provided. In the morning, I found the Royal Shakespeare Theater and bought a ticket for a play the following night.

After pushing for several days, Stratford allowed me to rest. I’m a sucker for the Tudor-style, black and white or black and tan, half-timbered buildings. In my mind’s eye, I have intended to build one for myself, though it gets ever-smaller as I age and my ambitions shrink. It fascinated me how buildings dating from the 1500s could now have indoor plumbing and neon lights.

I took some time for a peaceful hike, through fog, along the River Avon. I had much on my mind. The previous three months had raised the possibility that I had found my life partner. I met Vicki during my first quarter at UCLA. We had one class together, ‘Education of the Mexican-American Child.’ It would be the only education class I took there. I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to be a teacher, but with a History Major and English Minor, that could be a possibility. During my two years at UCLA, I tutored English to 4th grade immigrant kids in L.A. Chinatown. A year earlier, after deciding my years of competitive running were over, I went back to my high school coach, and he gave me the tenth-grade cross country team to try my hand with. We made it that year to the city finals. I’d enjoyed both of those teaching experiences.

At UCLA, though, I took a series of creative writing classes. A writing career interested me, but not if I needed to be ready to support a family. I knew too many starving writers. For a short time, I pondered studying for the pastorate. That would have been for all the wrong reasons, as much to figure out what I believed about God—if He existed—as to serve the God who might be there.

Then, on a lark, I took a Movement Behavior class, partly to better be able to describe my characters in fiction. The professor, Dr. Hunt, was teaching Kinesiology in the Dance Department, but as a physical therapist she had lived among and treated Bedouins, Inuit, and a variety of other cultures. She introduced a remarkable amount of anthropology. I was so blown away by what I learned that the following quarters I took every class she offered. In the process, I didn’t quite finish my minor in English, but I did complete one in Kinesiology. I began to ponder a career in Physical Therapy, until I realized I would need two years of math and science prerequisites before PT school. As I walked along the River Avon, I leaned toward teaching. Vicki was studying to be a teacher. Two teachers would have the same vacations.

At Thanksgiving of my first (junior) UCLA year, I mistook a reply from a young lady and incorrectly jumped to the conclusion that I was engaged. Between Thanksgiving and Christmas, I was checking my dorm mailbox multiple times each day, always to find it empty, but sometimes to see the student who was sorting the mail on the other side. I knew her slightly from my ‘Education of the Mexican-American Child’ class. On the first day of that class I did what all unattached students do, I glanced unobtrusively around the room, and thought to myself, “Nothing here.” She remembers whispering to Bonnie, her roommate, “Nothing here.”

They lived two floors above me and we often left for class at about the same time, so I occasionally walked them to the main campus, or saw them in the dorm cafeteria. At the end of the quarter, Tuesday of finals week was my 21st birthday, and I went home to celebrate with my parents and siblings. Back on campus, the next evening, a coed was stabbed to death in the parking structure not far from our dorm. The crime has been connected to the Zodiac Killer, and left the whole campus on edge. When the final exam for the education class got out after dark on Saturday evening, I finished early, but stuck around outside to walk the girls back to the dorm. I was still thinking about the girl from Thanksgiving, but I remember thinking that I hoped there was someone available to walk my future wife safely home. Little could I have imagined.

We had to move out of the dorm for the Christmas holidays. My parents came to help me transport my things, and while Dad and I made several trips up and down the elevator, my mother—who could strike up a conversation with anyone—chatted with the nice young woman who worked behind the desk, who seemed to know me.

I do not remember what play I saw at the Royal Shakespeare Theater that night. What fascinated me most was the way the set could be staged with almost no scenery. Instead, sections of the stage itself would rise or fall, high to become the bow of a ship, or less to become a bench. However, I could leave and say that I had seen a Shakespeare play at Stratford-upon-Avon. I walked back to the Youth Hostel ready to leave in the morning for Ireland. Admittedly, that was in the opposite direction from France.

Once, for a session of the Movement Behavior class, Dr. Hunt took the students to a large, walled-in, grassy area behind the Women’s Gym. Our assignment was to move. Just move. After a while, she called us in and she reported what she had seen. The class was heavily dance majors, and she’d observed the way many of the students had picked a spot and waved arms and legs or done a variety of artistic contortions. Then she got to me, and chuckled. “Brian, you explored every inch of grass and every corner.” I didn’t realize it yet, but that would describe my trip to Europe.

Labels: 1972, Anecdotes, Europe, History, Memoir, Teaching, The Writing Life, Theater, Travel, UCLA

Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #2

Saturday, September 17, 2022

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

I had an address for a bed and breakfast in Earl’s Court, a mere 32 miles away. I had walked that far in a day previously so even after I realized my mistake, I was not concerned. I had hiked the high Sierras. I ran run cross country in high school and my first year of college. I’d run a marathon in Mexico. I once got my high school class to challenge the class just ahead of us to a contest to see which class could rack up the most total laps on a Saturday, and personally tallied 33 miles, so I set out on a beautiful sunny morning to walk to Earl’s Court. I probably walked past dozens of bed and breakfasts that would have served me well, but a friend had given me the address of the place he’d stayed in Earl’s Court.

First time travelers may be struck by the fact that a foreign country appears in the same colors as at home, but somehow looks different. I was pondering that when a car stopped and a young man offered me a ride. I gladly accepted, and obeyed his instructions to stow my rucksack in the boot. Do you know that the British drive on the wrong side of the road? They also seat the driver on the wrong side of the car. I had read about it, but now I saw this peculiarity verified.

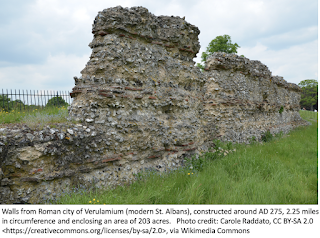

When my benefactor learned that this was my first day in England, he decided to divert and show me some local Roman ruins. We had a most congenial time, and then he let me out to continue on my way. The countryside gradually gave way to industrial areas, and then brownstone residential areas, and then I was in Earl’s Court. I had successfully flown across an ocean, walked most of 32 miles, gotten some exercise (though not much to eat), met a native, seen some Roman ruins, and located a target address. I decided I ought to recount my safety and my successes in letters to Vicki and my parents.

Of course, I had no return address to offer them other than the bed and breakfast in Earl’s Court, and it would be two weeks for my letters to get to California and receive answers back (Note to those who grew up in the age of email and texting: Letters were a thing that allowed Neanderthals to communicate over long distances, albeit very slowly). On the plus side, those two weeks would allow me time to visit Ireland before continuing to France, where I would hunker down with my novel and the French language. I still entertained that objective.

A few thoughts from 50 years later:

After yesterday’s episode, I messaged with a high school friend who did her travel with the army, as a nurse, and though she did not go to Vietnam, the topic came up in our discussion. For my generation, it often will. For my cohort, our post-high-school years were either spent in Vietnam or trying to stay out of Vietnam, or maybe protesting in the streets over Vietnam.

Like many of my peers, I was conflicted about Vietnam. I loved my country and wanted to defend it, but questions nagged me about whether in Vietnam we were the good guys or the bad guys. I started college three days after high school, not because I wanted to avoid the draft (Note to those who grew up in the era of an all-volunteer army: It used to be that when the letter from the draft board arrived, you reported for military duty). In 1968, the best way to stay free of the draft was to stay in school. Although I did want to avoid the draft, my primary motivation for college was excitement about college. However, those first weeks, I buddied around with a friend who really wasn’t that excited about school. Toby dropped out, got drafted, and died standing in the boot camp breakfast line. A recruit standing behind him dropped his rifle.

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

The spring I was finishing up at community college and getting ready to transfer to UCLA, the employment office connected me with a middle aged veteran who needed a man Friday. Pat suffered from emphysema, due to an accident in the Air Force. He knew he was dying, and wanted to do so in Europe. My job would be to carry his oxygen tank, and then accompany his body home at the end. He would pay all of my expenses and a nice salary. Most importantly for me, it would be my longed-for trip overseas. I look back on that episode as the supreme test of my transition to adulthood. Going with Pat would mean I would have to cancel my plans for UCLA. Pat told me Sen. Cranston owed him some favors and could fix me up with the draft board. Although I didn’t want to go to Vietnam, I also didn’t want some politician pulling strings for me. I drove Pat to Cranston’s office, but the Senator had been called away that day. Pat was expecting a big check from the government, but I began to wonder if it was actually coming. Pat liked to brag about the friends he looked forward to seeing, but from his description, some of them impressed me as a little shady. He also talked about the girls he would be able to get me, and how they could move in with us. That wasn’t the kind of girlfriend I wanted. After investing five or six months in Pat’s dream, and as much as I wanted to see Europe, I realized that I wanted to be my own boss when I traveled. I told Pat I was going to UCLA. To have gone with Pat then would have traded away everything of value that I have today.

I remained timid and indecisive about the war. I took part in a few demonstrations, and wavered over the question of what to do if drafted. I could not imagine killing another human being. Maybe I would go in as a medic. Maybe I would go to Canada. Dying for my country was one thing, but what if our side was actually the bad guys? That would be worse than dying in the boot camp breakfast line.

One more friendship stands out: I had written a 500 page—typed, double spaced—murder mystery (Note to those who learned word processing at a computer key board: Word-working was once done at a manual instrument that left one’s fingers raw and swollen at the end of the writing day). I had alternated 12-hour writing days with days carting Pat around. UCLA had a novel writing contest that first quarter and my 500 pages lost to a Vietnam vet’s 30-page opening chapter. Brian Jones took his $5,000 prize, went home and beat up his wife. The prize went for her hospital costs and the divorce. Over the next two years that I had to get to know him, I watched the Man Who Had Everything slowly fall apart.

We did not understand PTSD in those days, nor PITS (Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress), a concept first described by Psychologist and Sociologist Rachel MacNair. As I heard MacNair present at a conference in 2019, and then driving the carpool back to our shared AirB&B, she put into words exactly what I sensed had happened to Brian Jones. Brian had been the All-American everything: football quarterback, Student Body President, going steady with the head cheer-leader. Then he had done the All-American thing to do in 1966; he joined the Marines. When I asked about his experience in Vietnam, he could only shrug and say, “I killed a lot of Gooks.” There is PTSD trauma that soldiers experience when bullets are flying and friends all around them are dying, but PITS kicks in when someone raised with high moral values must face that they have become a murderer. Within a few months of my return from Europe, Brian Jones drove a van full of marijuana over a cliff, while running from police.

I believe I have seen PITS twice more. For a while I was visiting and corresponding with an inmate on Death Row in San Quentin Prison. He had been convicted as a serial killer. Independent research brought me an account of a childhood murder-dismemberment (of his mother) in which he had been forced to participate. Every one of his murders had been a reenactment of that event.

And then, in helping a friend clean up after a tenant, I found the letter-to-herself of a woman whose life had spiraled down after an abortion. Her agony came out in one haunting line, “This is not who I am!”

In 1972, as I left for Europe, the United States was struggling with a similar disconnect. “This is not who we are!”

Labels: 1972, Abortion, Aviation, Europe, Friday 10:03, History, Memoir, Milestones, The Writing Life, Travel, UCLA

Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #1

Friday, September 16, 2022

Fifty years ago, today, I boarded a flight in Los Angeles and flew to Luton, just north of London, UK. Thus began the great coming-of-age adventure of my life. My mother and my then girlfriend (Vicki, who has now been my wife for 49 years) saw me off at the airport. In flight, I remember the Rocky Mountains covered with a layer of golden-yellow Aspen trees, ice chunks floating in Hudson Bay, an hour in a duty-free shop beside a snow-cleared runway in Iceland, and the first rays of daylight as we took off from Edinburgh. I was 22, and—unlike today—I had been able to work my way through UCLA with no debts, and graduate with $1,000 in the bank.

I did not walk in the graduation ceremonies. Skipping those expenses gave me another hundred dollars for my voyage. Instead, I walked from my last final exam to a student travel agency and bought my one-way ticket to Europe. The other choice had been Japan, which interested me more, but five years of French would serve me better than my three quarters of Japanese. It was my plan to sojourn for a year in Paris. I would work on making my French useful, and write on the novel from which I had already shown Vicki portions over a year earlier. My last quarter at UCLA had been exhausting. During registration, a counselor pointed out that I had accrued 207 units, and once I went over 208 without graduating, I would not be allowed to register for another quarter. I had transferred in from community college with more than the usual totals, and then decided to add a kinesiology minor and creative writing classes to my history major. I also, wanting to explore what eventually became my career, took the ‘Education of the Mexican-American Child’ class in which I met Vicki. The gist of it was, to complete all my graduation requirements, I needed to take and pass 28 units my final quarter. I may have set the all-time UCLA record for most units to earn a BA. As I returned to campus after buying my ticket, I looked out on the sea of peers who were practicing for the ceremony. Was there even one person I needed to say 'goodbye' to? Vicki came to mind. Our almost-two-year relationship had been friendly, but not romantic, and I did not see much chance that I could find her in the crowd. I did see her roommate, who promised she would pass along my goodbye. My main activity for the summer would be two volunteer sessions as a camp counselor, one with teen diabetics and the second for kids who came largely from Los Angeles Chinatown, where I had been tutoring English during my time at UCLA. One preparatory task for that was interviewing the families for each camper. One of those families spoke only Spanish. I had not yet begun the Spanish which would later serve as my almost-competent second language, so I called Vicki and asked if she would translate for me. On a Saturday morning I picked her up and we drove to Chinatown, but the family was not at home. I knew there was an Asian-American culture fair going on that weekend at nearby Echo Park, so we went there to kill some time. The family still wasn’t home, so we drove to USC, where Vicki would be taking classes for a teaching credential. We did a lot of talking. By the time I got her home in the late afternoon (unbeknownst to me, she had a date she needed to get ready for), I had begun to rethink our relationship. We had a wild summer. By the time Vicki and my Mom dropped me off at LAX, I was much less sure that I wanted to be gone for the full year. As we parted, I whispered, “I’ll be home for Christmas.”Labels: Aviation, Europe, Friday 10:03, Language Acquisition, Light at the End of the Tunnel, Memoir, Milestones, Teaching, The Writing Life, Travel, UCLA

Back to Normalcy after a Rabbit Firestorm: Anatomy of a Capers Chūnyùn

Saturday, February 05, 2011

World-wide, Chinese New Year is celebrated by Spring Festival and Chūnyùn (春运), the greatest annual migration on earth. In 2008, the 1.3 billion Chinese took 2.2 billion train trips within the 40 day travel window. The celebrations include feasting, fireworks, dragons dancing in the streets, and time with family and friends. Apparently, also, they google the phrase Xin nian kuai le.

World-wide, Chinese New Year is celebrated by Spring Festival and Chūnyùn (春运), the greatest annual migration on earth. In 2008, the 1.3 billion Chinese took 2.2 billion train trips within the 40 day travel window. The celebrations include feasting, fireworks, dragons dancing in the streets, and time with family and friends. Apparently, also, they google the phrase Xin nian kuai le.

I know this last detail because over the past six weeks, this blog has been celebrating its fourth annual Capers Virtual Chūnyùn. I began seeing traffic pick up in mid December, helping to make that my most-visited month ever. Traffic continued steady through January and then spiked on Saturday the 29th. For the first time in the blog's six year history, page views topped 1,000. All by itself, Wednesday—Chinese New Year—brought 429. Five days into February, its totals now exceed all of January. Just four days this week, Monday through Thursday, out-performed the whole four month period, April to July.

Credit Google.

I'm assuming the vast majority of my traffic came from overseas Chinese. This past month, if Sweden’s nearly 13,000 Chinese expatriates went to google.com.se and searched for Xin nian kuai le, they got 272 000 results, of which my 2008 New Year’s greeting was listed 2nd. The United Arab Emirate’s 180,000 Chinese found me 3rd, and sent me 29 hits. Also at 2nd, Singapore’s 3.6 million found me 300 times. Myanmar’s million-plus found my 2008 message 4th and December 2010 update 5th. They made 139 visits. The UK’s 400,000 Chinese clicked on me 111 times. None of my visitors clicked in from China itself, but there, “新年快乐”would be far likelier to get lost in the crowd than would Xin Nian Kuai Le in the Diaspora. That and 2010 saw Google and China tangle, with a reduction of Google’s presence.

When all these numbers began to develop, my first reaction was awe over the chance popularity of an almost-throw-away post from three years ago. It struck me as random and surreal. Then, as I studied the source locations, I was transported back forty years, to a time in my life before marriage into a Spanish-speaking family, nine years living in Colombia, and 20 years teaching recent immigrants from Mexico. My focus on Latin America and its immigrants had interrupted an earlier interest.

I mentioned in my recent post on Fred Korematsu Day that I took at class at Pasadena City College called Sociology of the Asian in America. I took it because, even in high school, I had an interest in immigration and the mixing of cultures. Over the course of completing a history major, whatever class I might be taking, I wrote about Asian immigration into the Western world. I wrote about Japanese in Mexico, Cuba, Peru, and Brazil, and especially, I wrote about the Chinese in Europe. During three quarters of independent study at UCLA, I wrote what I believe was the longest treatment of the Chinese in France that then existed in English (it has since been surpassed).

As blog hits came in from Holland, Germany, Luxembourg, Italy, Spain, and Sweden, I was once again looking at the Chinese in Europe, and a Diasphora that now includes places like Dubai and Nairobi (I showed up 4th at Google Kenya).

I’m not sure yet what conclusions to draw, but I find myself thinking again on this subject after many years away from it. I am also beginning to read When a Billion Chinese Jump, by Jonathan Watts. Stay tuned. My thoughts in this Year of the Rabbit may turn increasingly to China, and its Diasphora. Watts’ premise is that any race to stave off global warming and worldwide ecological disaster will be won or lost in mainland China. The same may be true in a wide variety of human activities. I am fortunate to have friends both inside and outside of China, and about two months of Chinese travel experience. That doesn’t rank me yet as an expert, but it gives me a place to start.

Happy Year of the Rabbit

Notes:

On Chūnyùn. On the Chinese Diasphora, and the Chinese in Europe.

Disclosure of Material Connection: The link above is an “affiliate link.” This means if someone clicks on the link and purchases the item, I will receive a commission. This has never happened yet, and would only be a pittance if it did. For this reason, I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.”

Labels: Blogs, China, Europe, History, Immigration, Japan, Teaching, Travel, UCLA, Websites, Xin Nian Kuai Le

A Civil Fred Korematsu Day, to You and Yours

Saturday, January 29, 2011

Tomorrow will be Fred Korematsu Day, as will January 30th in all future years, declared so by Governor Schwarzenegger and the unanimous desire of both houses of the California Legislature. Parallel days in Oregon or Washington might honor Minoru Yasui and Gordon Hirabayashi. In my own mind, it will be Jiro Morita Day, and by extension—like a Rosa Parks Day or a César Chavez Day—it will be a time to reflect on how citizens in a supposedly civil society can respond at those moments when civility is in jeopardy.

While I was growing up, each of my parents spoke of the pain and confusion they felt in 1942 when their Nisei classmates were sent away to government “Relocation Camps.” Later, while I was taking a year of Japanese language at Pasadena City College, the school offered “Sociology of the Asian in America.” The course might qualify among the ethnic studies courses that have just been outlawed by the state of Arizona, but I look back upon it as one of the most fruitful classes I ever took. Three hours one night a week, with a 20 minute break, I quickly began spending those twenty minutes—and the walk to the parking lot after class—with Jiro Morita. At 80, he told me he was taking the class “to stay young.”

I spent every possible moment asking about his long life.

In early 1942, when the United States government was preparing to lock up the entire Japanese community on the west coast, the Japanese themselves worked through intense debate over how to respond. Poet Amy Uyematsu, Mr. Morita’s granddaughter, writes,

Grandpa was good at persuading the others

after the official evacuation orders.

Detained at Tulare Assembly Center,

he was the voice of reason among his angry friends,

raising everyone’s spirits

when he started the morning exercise class.

(From “Desert Camouflage,” in Stone Bow Prayer)

Most of the issei (1st generation immigrants) and nisei (2nd generation/US citizens) decided that obedience to the government’s order would offer their best long-term hope for full integration into American society. Three American-born young men, however, decided to test their 14th Amendment rights and protections. Korematsu, Hirabayashi, and Yasui performed that most-American of exercises: they took it to court.

Korematsu (1919 – 2005), born in Oakland, first tried plastic surgery and a name change to evade the order for Japanese to report for relocation. When that failed, he agreed to let his arrest be used as a test case. Korematsu remained at the Topaz, Utah, internment camp while Korematsu v. United States worked its way to the Supreme Court. They decided against him, 6-3.

Although Korematsu was an unskilled laborer, both Hirabayashi (b. 1918, in Seattle) and Yasui (1916-1986, of Hood River) had earned bachelors degrees from their state universities. Yasui even held a law degree and the rank of second lieutenant in the U.S. Army's Infantry Reserve. The relocation order was preceded by curfews, which each man intentionally violated before surrendering to authorities. Eventually the Supreme Court linked the two cases and rendered a unanimous decision: The government had the authority to order detention and relocation of even U.S. citizens under its war powers. Korematsu’s conviction was not overturned until 1983, Yasui’s until 1986, and Hirabayashi’s until 1987.

Source

In the early 1970’s, I had a brief, chance meeting with Gordon Hirabayashi. During my two years at UCLA, I studied additional Japanese language and a year each of Japanese and Chinese history. I also volunteered as an ESL tutor at Castelar Elementary School (L.A. Chinatown), and as a summer counselor for an Asian session of Unicamp. This took me often into the Asian American Study Center, where Elsie Osajima, Mr. Morita’s daughter, was an administrative assistant. Once, when I entered Mrs. Osajima’s office on some errand, I found several people chatting with Mr. Hirabayashi. It was very like a similar meeting, during the same months, and no more than 500 yards apart, with former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Earl Warren. In each case, I knew it was a rare privilege to connect with an important moment in history, and yet the situation didn’t allow for me to ask questions. On the spur of the moment, I couldn’t even think of any.

However, the two meetings provide an interesting juxtaposition. Earl Warren, as Attorney General of California, was the driving force behind convincing President Roosevelt of the necessity for removing the Japanese from their homes and communities. The same Warren Court (1954-1969) that did so much to advance civil rights in so many other areas also could have been the court to reverse Korematsu, Hirabayashi, and Yasui. It didn’t. What my parents identified immediately as wrong when their high school chums were hauled away in 1942, the federal courts only caught up with in the 1980’s. Then, California recognition had to wait until 2011.

If there is a lesson in Earl Warren’s life, it is that for any community, prejudice is easiest to see from outside the area, or outside the era. Warren could see the prejudice against African Americans in the South, yet at the same time, he was either blind to, or unwilling to face prejudice against the Japanese in California. This brings us back to Arizona, today, and the efforts to redefine citizenship. Fred Korematsu looked back on his own case and pursued justice an a reversal of the court's decision, not for his own sake, but so that the United States could be counted on to give the 14th Amendment guarantees to every person ever born or naturalized in the United States, and in whichever state they might reside.

May it ever be so.

As I prepared this post, the miracle of Google allowed me to connect with Amy Uyematsu and Elsie Osajima. I intend soon to write more about Jiro Morita. He was an amazing man.

In the meantime, enjoy a civil Fred Korematsu Day. Pick an injustice, and ponder how to alleviate it.

http://www.amerasiajournal.org/blog/?p=1840

http://www.amerasiajournal.org/blog/?p=1840Additional Resources:

Korematsu v. United StatesHirabayashi v. United States

Yasui v. United States

Ex Parte Endo

In this PBS video, Mr. Korematsu tells his own story.

This book targets readers from 3rd to 6th grades.

This book targets grades 7 through 10. Although it appears to be out of print, used copies may be available. Perhaps, now that California has an annual Fred Korematsu Day, it will be reprinted.

Gordon Hirabayashi - On the Day of Remembrance: A Statement of Conscience

Gordon Hirabayashi - On the Day of Remembrance: A Statement of ConscienceIn this nearly-two-hour from 2000, Gordon Hirabayashi discusses the Japanese Evacuation and its importance to history.

Disclosure of Material Connection: The Amazon links above are “affiliate links.” This means if someone clicks on the link and purchases the item, I will receive a commission. This has never happened to me as of today, and would only be a pittance if it did. I have no financial arrangement concerning any of the other materials I have linked with. I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.”

Labels: Anecdotes, Bilingualism, California, Famous People, History, Immigration, Japan, Memoir, Milestones, UCLA

Election 2010: Marijuana turns me into a Marxist

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

By my title, I don’t mean that smoking it (never have, never will) sends me scurrying for my Mao cap and Ché t-shirt. Rather, in puzzling out how government should treat marijuana, I am very sensitive to social class differences. The Haves with whom I attended UCLA could close their dorm rooms Friday evenings, toke up, and still graduate and go on for their MBA’s. But among the heavily Have-not population where I teach, hop-heads have neither such security nor such safety net. They often fail to graduate from junior high. They become parents while attending a few years of continuation high school. By young adulthood, too many are on to harder substances, in prison, or dead.

Thus, as I come to a study of California Prop 19, the Regulate, Control and Tax Cannabis Act of 2010, which seeks to relax marijuana laws, I need to make it clear that my sentiments are middle class and my sympathies are for kids growing up in poverty. Rich kids will hire lawyers and avoid jail time. The rich and upper middle can afford to indulge in the so-called “victimless crimes,” while those same behaviors create victims to the third and fourth generation among the poor.

Secondly, I need to point out the sorry history of Nullification. Pennsylvania farmers announced they would not pay the whiskey tax, and Washington and Hamilton stomped them. Jefferson and Madison toyed with the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, and lost. Calhoun said South Carolina would not collect the federal tariff, and got swept aside. The Civil War should have settled this question for all time, but for good measure, Orval Faubus stood in the school-house door to block federal integration, and Eisenhower sent the US Army to escort the incoming students to their classrooms. Drug policy, like that for immigration or marriage, needs to be set on a national scale. A single state may set more stringent rules (for example, California’s laws on greenhouse emissions), but can never set the bar lower than the federal laws. Federal policy should never be set by an initiative in California, the legislature in Arizona, or the Supreme Court of Massachusetts. Passage of this proposition on Nov. 2, will open many years of litigation on Nov. 3. Californians would be setting themselves up to forfeit untold federal dollars by drawing a marijuana Mason-Dixon Line at the Oregon, Nevada, and Arizona borders.

The practical purpose of this proposition then must be seen as leverage: California, a state with 53 congressmen, goes on record in opposition to the federal law. California, owner of a 10.2% share in the Electoral College, will now have the right to ask any visiting presidential candidate what he or she plans to do to remedy the situation. Maybe we would start a bandwagon effect. Maybe down the road we would see change in the federal law. There may or may not be merit in this argument. California voters have twice passed defense-of-marriage initiatives, with the total number of states that have passed traditional marriage constitutional amendments topping 30. Thus far, however, I see no congressional momentum for national legislation. This would seem to undermine the argument in favor of leverage. Any readers who have come this far looking only for my recommendation on Prop 19 may stop here. Proposition 19 is rejected as out of order.

Nevertheless, the subject having come up, I have a few additional thoughts over a full, federal legalization of marijuana. The best reasons have very little to do with California, at all.

Personal experience #1 – I walk into a restroom and the twelve-year-old is quick enough to flick his joint into the toilet tank, but a little too tipsy to correctly manipulate the handle. The ten year old is blurry-eyed and can only stammer bad answers to my questions.

Personal experience #2 – I discuss Prop 19 with five classes of 7th and 8th graders, and ask midway through each what it probably costs in our area for a kilo of marijuana. Five consecutive classes each settle quickly in the $450 ballpark. I have no way of knowing if they were correct, but the agreement was startling, and every class knew whom to turn to as the in-house expert.

Personal experience #3 – Juan, teacher in a thatched-roof jungle school house and a friend from my days in Colombia, is pulled from his classroom by drug-financed revolutionaries, taken to the village square, and shot, only because he serves in a government school.

From the first two experiences, I learn that whatever we’re currently doing has only limited success among the 12 or 14-year-olds I care about and can put faces to. The truth is, most of my students are clean. And for the minority who are using, the marijuana is probably a symptom—not the origin—of their pathologies (though it may serve as an accelerator). Even, though, at some $450/kilo, and when we know it will be a curse on their lives, we are currently incapable of keeping it out of their hands.

But I have experience at both ends of the pipeline. As Haves, our buying power has the ability to destabilize any number of Have-not nations to the south of us. I can remember life in Colombia during a couple of years when drug cartels assassinated a judge, on average, every other week. Over the last decade and a half, Colombia has reestablished a fair degree of order, but the price has been a government willing to overlook thousands of extrajudicial killings of mostly Have-not peasants by mostly Have “self-defense” forces. For two decades, the US has been funding one side of the civil war with military aide and the other side of the war with our appetite for “victimless” recreational highs.

Proponents of Prop 19 argue that decriminalizing marijuana will save us enormous sums of money, redirect police attention toward violent crime, and provide a windfall in taxes. I believe all three claims rest on doubtful assumptions, but we have been suckered by such promises before. The state lottery, we were told when we voted for it, would dry-up illegal gambling and insure great wealth for our schools. Instead, it has saddled Have-nots with a massive regressive tax, trained up a clientele for a vibrant-but-untaxable underground gambling industry, fostered a get-rich-quick mentality that helped fuel the housing bubble, and left us with schools that are starved for basic necessities.

However—and I offer this very tentatively—a reevaluation of our entire national drug policy (not a substance-by-substance approach) might make sense as an act of neighborly concern. Our Have drug appetite today is financing war in Have-not Mexico between over-funded thugs and an under-funded government. Legalizing marijuana (and thus reducing its price [and then you would also have to consider the likes of cocaine]) might take the lifeblood away from a criminal element that has become a force unto itself inside our closest neighbor.

I know, I’m talking like a Marxist.

Labels: 2010 Elections, California, Colombia, History, Immigration, Mexico, Politics, Teaching, UCLA

A Little Memory of John Wooden

Saturday, June 05, 2010

Many people who knew John Wooden much better than I are recounting stories of him today, and I have no original pictures. But I can’t let his passing go completely unmentioned here. Wooden graduated to Heaven yesterday, at 99.

Many people who knew John Wooden much better than I are recounting stories of him today, and I have no original pictures. But I can’t let his passing go completely unmentioned here. Wooden graduated to Heaven yesterday, at 99.

The last time I saw John Wooden was spring of ’72. He came out a side door at Pauley Pavilion, just as I approached, and he gave me a little smile and nod of his head. It was the same door I’d seen Haile Selassie exit from four years earlier, but I’d gotten neither a smile nor a nod on that occasion. Selassie was the reigning emperor of Ethiopia. Wooden, the “Wizard of Westwood,” was the reigning king of college basketball. He’d just won the 8th of his eventual ten NCAA National Championships. At UCLA, his genius was more recognized than any of our Nobel Prize winners. If it had been his nature to be as imperial as Selassie, he had earned the right.

Wooden had given a guest lecture a few weeks earlier in one of my kinesiology classes, but I can’t imagine he still recognized me. I was just one of 35,000 students at UCLA., but more than anything else, Wooden was a teacher. All 35,000 of us were his students, and I got a smile.

I’ve read that after ten national championships he was most proud that his teams ranked highest in number of athletes who actually graduated. I became acquainted with some of those young men, Terry Schofield, Sven Nader, and Keith (later, Jamaal) Wilkes. He recruited athletes of fine character, not just physical prowess. Among his many personal accomplishments, he was proudest of winning the Big Ten Academic Achievement Award (during the year he also led his team to the conference championship) for the highest GPA. He was a remarkable man, a gentleman scholar, and a servant of God, and I was blessed by the little bit he touched my life.

(In poking around on the web, I find this interview with Wooden, in which he quotes a poem written by Sven Nader. Nader lived in our dorm during my sophomore year [as did Wilkes, Bill Walton, and the rest of the freshmen team]. I remember Sven's beautiful singing voice. Seven-footers have a lot of lung capacity.)

Labels: Anecdotes, California, Christian Worldview, Famous People, Milestones, Sports, Teaching, UCLA

Bo Diddley is Gone (but his riff lives on)

Tuesday, June 03, 2008

Bo Diddley died yesterday, at 79.

These days, I think of Bo Diddley most often because at church we occasionally sing a worship chorus that starts with a classic Bo Diddley rhythm. BUM-pa BUM-pa…pa-pa-pa-pa-pa BUMP. I'm not sure our young drummer even knows the riff's source.

But in the late 1960's, while I was in high school and community college, Bo Diddley’s music was a staple on the L.A. Top 40 station I listened to. Diddley himself lived about half-way between my house and Granada Hills High School. It was only about a block off the route I walked every day to classes. In late ’68 or early ‘69, a girl I knew told me she was taking guitar lessons from Diddley, and invited me to go with her to one of his concerts.

At the time, Bo Diddley was one of the most famous people (see also: Rockefeller) this eighteen-year-old had ever chatted up. (A year-or-so earlier, I had been within a few feet of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, when he spoke at UCLA. However, the Emperor didn't exactly exude approachability.) My friend and I knocked on Diddley’s door, and he opened it, dressed only in his underwear. It didn’t seem to faze the young lady, so I figured I could play along. Diddley welcomed us and invited us in. Now THAT’s approachability.

We made small talk while he finished dressing and fixed himself a sandwich. Then we rode in his limousine, through an incredibly foggy night, to the concert hall. I remember being told it was in Torrance, but in that fog, it could have been anywhere on the North American continent. It was a cavernous building, with no furniture. In a previous life, it might have been a warehouse. The crowd was mostly seated on the floor, with just a few people dancing in the far corners.

We sat back stage and chatted during the opening acts. Then we went out to watch during Diddley’s set. The crowd loved every song. I loved every song. It was probably a 45 minute performance. Afterwards, we were back in his limo, and home. The young lady and I never dated again. She’d given me a peek into the world she longed to conquer, and though it was a marvelous peek, it wasn’t the world in which I wanted to live my life.

But sometimes, even today, I catch myself singing BUM-pa BUM-pa…pa-pa-pa-pa-pa BUMP. Bo Diddley may be dead, but his riff lives on.

Labels: Anecdotes, California, Famous People, Milestones, Music, UCLA

History of my novel, Friday 10:03 (Part 13)

Wednesday, April 16, 2008

(This series begins here.)

So it was my plan to rent a garret in Paris, practice my French, and write my novel.

The day of my last final, in June, 1972, I bought a one-way ticket as far as London, for September 16. I intended to spend most of the summer writing, with two ten-day breaks to volunteer at UCLA’s summer camp for underprivileged kids, UniCamp. I planned one session for elementary-aged diabetics, and a second for the kids I’d been doing ESL with in Chinatown.

What I hadn’t planned on for that summer was falling in love.

Vicki and I had been friends for 18 months. We'd even spent one day together at the beach (see Part 8), but I graduated from UCLA not expecting to see her again. However, for the Chinatown kids I was registering for UniCamp, I needed to interview the parents and I had one Spanish speaking family on my list. In those days I had some fumbling French and the barest beginnings of Japanese. But Vicki was fluent in Spanish and I’d left UCLA the last day regretting that I’d never had a chance for a proper goodbye.

We arranged to go together on a Saturday morning for the interviews. Events of the day conspired so that we had about ten hours to talk about deep things, and sometime during that day, I caught a glimpse of possibilities I’d previously ruled out. Long-story-short, we spent the summer investigating those possibilities. I did my summer camps, but I got very little writing done.

And when she accompanied me to the airport on September 16th, I told her I’d be home for Christmas.

History of my novel, Friday 10:03 (Part 12)

Saturday, April 12, 2008

(This series begins here.)

It has been almost three months since I posted Part 11 of this series, and three weeks since I even mentioned Friday 10:03. That is fitting. Over the four decades that I have been working on this book, I have several times gone years without writing a word.

During these three months, I actually have made considerable progress on the book itself. I reached 75,000 words (about 250 pages, probably 70% of the finished novel) and turned that over to David Anthony Durham, my thesis chair. I also had three shorter sections critiqued by other writers at Mount Hermon, and pitched the book to three different editors and two agents. David got back to me with a very thorough critique (Oy vey! Have I got a job for me!), and we agreed that rather than trying to first finish and then rewrite the whole book (a thesis only needs to be 120 pages), I would rewrite a portion of what I already have, be done with the thesis, and finish the novel with my degree in hand.

But now, with the current events updated, our history must jump back to 1972, the year I graduated from UCLA. I did not even bother to walk in the ceremonies. Instead, I walked out of my last final and went directly to a travel agent. There I bought a one-way ticket to Europe. It was my plan to rent a garret in Paris, practice my French, and take a year to write my novel.

Little did I know.

Great Earthquakes I Have Known: Quake #1, San Fernando (Sylmar) 1971

Monday, March 03, 2008

After I wrote about all the earthquake activity around Guadalupe Victoria, Baja California (which had another 5.0 the next afternoon), Caedmonstia asked, “How big does an earthquake have to be for people to feel it?” Someplace, I’m sure there are wonderful scientific answers to that, such as, “It depends.” But I am thinking more experientially. In this new series, I will be describing the Standout Moments of My Personal Seismological Memory:

San Fernando, California, Feb, 9, 1971, 6:01 a.m., (6.6 on the Richter scale). I was about twenty miles away, on the 5th floor of a UCLA dorm building. It woke me up with the thought that a railroad train was coming through the bedroom. Those who were coherent enough to run to the windows reported seeing a wave of green explosions as transformers went dead across the still-dark city. Sixty five people died in the earthquake (most in one hospital that collapsed). The quake was much worse at my parents' house (a freestanding cabinet fell across my sister and her bed), only about ten miles from the epicenter and downstream from a large earthen dam. For me, it was the only time I ever remember everybody being awake and in line for breakfast when the dining hall opened at 7:00. But for what? Classes were canceled. I had been tutoring ESL at Castelar Elementary School in Chinatown, but the main building was sufficiently cracked that it could never be used again. A mile south of that was the Hall of Justice, which included both the DA’s and Sheriff’s offices, courtrooms, and several floors of jail. It also suffered damage and had to be evacuated and boarded up. It still stands empty, today. That made it difficult for me to research it when I wanted to use it as a location for my novel, Friday 10:03. Eventually, I talked to my father's cousin who had worked there, and it became one of my favorite locales in the book.