Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #10

Saturday, November 05, 2022

The night ferry from Dublin brought me to Holyhead, at dawn. From there I set my feet for London, hoping to find waiting mail. The Welsh countryside was beautiful, and the street signs entertained me with names like Llanfairpwllgwyngyll, Glyndyfrdwy, and Brynsaithmarchog. Holyhead sits on an island, connected to the British ‘mainland’ by the world’s oldest major suspension bridge.

It was a pleasant day. By walking some and getting a few rides, I covered about 150 miles before sundown.

I only skirted the outlying districts of Birmingham, rendered magical by yellow street lamps in a slight fog. I don’t remember where I thought I might get to spend the night, but a lorry driver stopped and offered me a ride. I’ve had readers in the British Isles for eleven days now, so we might as well use the correct vocabulary. There are no truck drivers in England, only lorry drivers.

We drove the M-40 the rest of the night, and the conversation was good. Not long before dawn, he dropped me on the outskirts of Winchester, and I rolled out my sleeping bag in a recently mowed cornfield. I might have slept a couple of hours, and the sun was up when I awoke.How often does one get to Winchester? I thought I ought to get a look at the famous cathedral before I returned to my pursuit of any letters waiting for me in London. As an inveterate whistler, as I walked I whistled The New Vaudeville Band’s 1966 whistling hit “Winchester Cathedral.”

I walked naively into Winchester and took a nice look at the first big church I came to. Yeah, it was nice, if maybe not worthy of all the hype I had heard. Then, thinking I could check-off Winchester from my bucket list, I started across the city to reach the highway north. In the process, I stumbled upon the C*A*T*H*D*R*A*L. Boy-oh-boy. The laugh was on me.

I spent a goodly amount of time properly appreciating an amazing feat of architecture, built between 1079 and 1532. The interior length runs a football field and a half, with burials from an even earlier building, as far back as Cynegils, King of Wessex (AD 611–643). More recently, the Cathedral contains the remains of Jane Austin

When finally I had seen enough of the Cathedral—and seeing on the map that I was only a couple of miles from Tichborne—I hiked out of Winchester on the M-31.

In England, I could not have repeated the details, but I recognized the name had been important on my family tree. Refreshing my memory as I write this, John Tichborne (1460 - 1498), born at Tichborne, had one son, Nicholas (b. abt. 1480 and recorded as “Burgess of Hindon,” living at Tisbury, about 50 miles west of Tichborne) who sired Dorothy (abt. 1510 - abt. 1572), who married John Sambourne. Their grandson Richard (1580 - abt. 1632) married Ann Bachiler. After Richard’s death, their three sons crossed the Atlantic with their maternal grandfather, the Rev. Stephen Bachiler, and settled in Massachusetts, thereby planting my mother’s family in America.

Several days ago, when I began writing this episode, I had no idea I would be posting this on Guy Fawkes Day, nor any intension of mentioning the religious struggles of the 16th and 17th Centuries. Yet as I poked around on the web, it couldn’t help but come up.

Richard Samborne would have been distantly related to Chidiock Tichborne (1562 –1586), who was executed at age 23 for his part in the Babington Plot, a conspiracy by a small group of Catholics who hoped to murder Queen Elizabeth I, and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots. Chidiock left behind a wife, a daughter, and three poems that can still be found in print. Other than Chidiock, the Tichborne family were able to remain Catholic and even (by concession of King James I) retain as Catholic their family chapel inside the Church of England St. Andrew’s Church in Tichborne. On the other hand, the same King James I took lands and livelihood away from Rev. Stephen Bachiler, a “notorious inconformist.” There are hints that his Bachiler line arrived in England as Huguenot refugees from the slaughters in France. It makes sense that Stephen Bachiler (1561-1656) was an early proponent of the separation of church and state in American Colonies.

In Tichborne, I found the village library and went in, but had no idea what I might find, or how to go about it. Year’s later, I discovered Tichborne’s Elegy.

Tichborne’s ElegyMy prime of youth is but a frost of cares, My feast of joy is but a dish of pain, My crop of corn is but a field of tares, And all my good is but vain hope of gain; The day is past, and yet I saw no sun, And now I live, and now my life is done.

My tale was heard and yet it was not told, My fruit is fallen, and yet my leaves are green, My youth is spent and yet I am not old, I saw the world and yet I was not seen; My thread is cut and yet it is not spun, And now I live, and now my life is done.

I sought my death and found it in my womb, I looked for life and saw it was a shade, I trod the earth and knew it was my tomb, And now I die, and now I was but made; My glass is full, and now my glass is run, And now I live, and now my life is done.

After sitting in the library for a short time, I caught a ride into London. My strongest memory is passing Wimbledon. I don’t follow tennis, but I recognized the name.

Labels: 1972, Anecdotes, England, Europe, Genealogy, History, Memoir, Travel, Wales

Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #8

Friday, October 21, 2022

My short visit to Ireland—three days of hard travel—did not allow me time to get as far north as Sligo, from whence hailed my paternal great-great-grandfather Carroll, nor to get out of the car in Cork, which I incorrectly thought had been the birthplace of my great-great-grandfather Kelley. However, I did spend a delightful overnight in Limerick. I have to assume the city figures somewhere in my DNA. Here is a quick one that I wrote just today:

An illustrious PM named Lis Truss

Said, “No longer can I hold this trust.”

The greatest frustration

Is viscous inflation

But we shan’t dissolve Commons. It is this thus.

I’m unable to find a photograph of the Youth Hostel in Limerick, and I have only a vague memory that it was somewhere near the city center. In lieu of photographs, I will tuck in a sampling of limericks from my collection.

What I do remember is the uproariously fun discussion we had when we discovered that the 17 guests who gathered in the common room that evening spoke 14 different dialects of English. Between us, we represented Australians, Canadians, New Zealanders, Boston, Georgia, Texas, Scotsmen, Welsh, several areas in England, and—of course—the standard and correct English that we speak in California. Since everyone was traveling, we each had recent observations of the funny differences in the ways English speakers say things. In addition to a cheap and clean place to sleep, one of the benefits of the Youth Hostels is trading experiences with the other travelers. Often, many were coming from where I hoped to go next, and could give impressions and advice.

When we could laugh no more, an Aussie girl told me she wanted to go for a beer, but didn’t want to be the only girl in the pub. She offered to buy me a drink if I would be her escort. Had she not asked, I probably would not have thought to include a pub in my Irish experiences. I’m glad I did. It was quiet, but the atmosphere was friendly. She did turn out to be the only female in the room, but we enjoyed our conversation walking over and back, and each drank one beer.

For a day that started in Loo Bridge and included the Ring-of-Kerry, I was more-than-ready to turn in when we got back to the Hostel. Just a few days earlier, I had attended a play by the Royal Shakespearian Theater, in Shakespeare’s birthplace, Stratford-upon-Avon. As nice as that had been, now I was sleeping a night in the city that had given its name to the Limerick, the apex of English literature and culture.

Labels: 1972, Anecdotes, Europe, Ireland, Limericks, Linguistics, Memoir, Travel

Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #7

Thursday, October 20, 2022

After I decided to separate from Beat and Urs, I dallied awhile to let them get ahead. I enjoyed handfuls of ripe blackberries from the roadside, and then was offered a ride by four German youths in an already-full VW Bug.

Together, we drove through Waterford, Dungarvan, and Cork, not stopping at tourist sites, but stopping twice along the way at pubs. Each time these young men showed disappointment that such a pub would not be open on a Sunday morning. Therefore, they beat upon the door until they had roused the tavernkeeper. Once inside, one of my comrades would order a round of beers, and I would add a round of chocolates. Many years later, in Tashkent, I met a young Uzbek who immediately observed that all Americans liked to travel. I corrected him to say that all Americans who had made it as far as Uzbekistan probably liked to travel. Thus, I must be careful against drawing too great a generality, based only upon the two groups of Germans whom I had encountered in less than twelve hours. I will say only that my small sample suggested that one attraction to draw young German men to visit Ireland in late September, 1972, would be the Irish beer.

Between pubs, we stopped only to search out bushes. I might have liked to at least have gotten out of the car in Cork. My grandmother told us Cork had been the birthplace of her immigrant grandfather. We now believe that he may have sailed from Cork, but probably lived closer to Dublin. Either way, I did not see much of Cork. I did, however, begin to question the wisdom of riding with a slightly drunk driver, over narrow and curvy roads, with visibility limited by hedges of blackberries. I decided to thank them for their company and the ride, and to walk on from there alone, with my target a Youth Hostel at Loo Bridge.

As I write this, I struggle to remember the Youth Hostel at Loo Bridge. Searching for a picture, I find one taken by Klaus Liphard, two years after I was there. He notes, “Unfortunately, I have no memory of my stay there.” That may explain why Loo Bridge no longer has a Youth Hostel. I do remember walking into a small store nearby, buying some bread and cheese, and parting from the shop keeper with a cherry, “Have a nice day.”

He looked at me strangely, and then answered, “Yes, I suppose we do.” I was reminded of the observation by Winston Churchill that the US and Great Britain (or in this case, the Irish) are “two nations divided by a common language.”

Looking at the map the next morning as I was leaving Loo Bridge, my eye was drawn to a loop through the Ring of Kerry, on a road marked, “Scenic Route.” I later suspected that ‘Scenic Route’ was Gaelic for ‘No cars travel on this 110 mile loop.’

I was fooled, though, because between Loo Bridge and Kilgarvan, a middle-aged man and his mother picked me up, and were quite excited when I told them I was from Los Angeles. “Oh, you know our cousin, then!”

“Well,” I tried to explain, “It’s a big city.”

“Oh, but you would know him. He owns the chemist shop.” (Meaning: drug store)

At tea time, we stopped and laid out a blanket and a picnic basket. They were very apologetic that they had no milk for my tea.

After that, I walked about two hours without seeing any vehicle pass. I began to feel concern that the loop might take me several days, as beautiful as the scenery was. My steps were still headed south along the eastern side of the peninsula. After that, I would still face the trip north on the west. However, besides just the beautiful scenery, I was still chuckling over the couple with a cousin in LA and the shopkeeper who misunderstood, “Have a nice day.” I began to praise God.

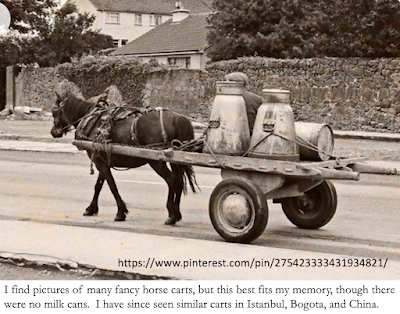

Almost immediately, I heard the clop of a horse behind me, and an elderly gentleman invited me up on his cart. I am still not sure what language he spoke. It may have been Gaelic, or it may have been English with a brogue too think for me to understand, but as much as we tried, communication was difficult. At one point, he tried very hard to express something. After multiple attempts, I figured out that he was referencing a certain flower that grew beside the road.

The rides I must have gotten don’t stand out in my mind, but I must have gotten some. I do remember walking one long stretch on the rugged western side of the peninsula.

However, I finished the scenic loop with enough time to catch a ride all the way to Limerick.

But Limerick is a story for our next episode.

Coming of Age, 1972 - Episode #6

Monday, October 17, 2022

After breakfast, I hiked with Beat (Bay-AHT) and Urs, from the Youth Hostel at Pwll Deri to the ferry landing in Fishguard. For a while we shared the road with a large flock of sheep heading the same direction.

The four-hour crossing from Fishguard to Rosslare, Ireland, was uneventful. We sat on deck in pleasant weather and talked. Beat and Urs were nineteen, and apprentice architects in the city of Basel. Beat spoke English more fluently than Urs, but he was also aggressively working to improve. He kept a note pad in his pocket, pulled it out anytime I used a word that was new to him, and would ask me about the word's meanings and use. My own attempts at language learning had suffered from a lack of just this degree of diligence, so I took note of how the process should be approached. Beat already spoke Swiss German, High German, and French; he was working hard on English; and during the time I knew him, he picked up some Italian and Hebrew. I had fumbled through five years of French and a year of Japanese, but from watching Beat, the Spanish studies I would begin soon after I returned from Europe promised more success.

We landed at Rosslare, and went through immigration. Then, after we were in the parking lot outside, another agent came running after us. He had a spray canister to treat our boots, and told us that Wales was experiencing an outbreak of hoof-and-mouth disease.

From Rosslare we walked into the city of Wexford, where we bought a few groceries in a small store, and asked for directions. Beat had seen mention of a campground, but by the time we reached it, the gate had been locked for the night. We rolled our sleeping bags out in the field beside the gate, and went to sleep.

At about midnight, a car pulled up at the gate. The German youths who manned it demonstrated recent indulgence in alcohol, which would not have bothered us, except that when they could not get into the campground, they decided to drive circles in the tall grass that hid us in our sleeping bags. Beat and I stood up, waving our arms. Meanwhile, Urs slept peacefully. The Germans did stop, about twenty yards short of running us over. Then they retreated to the far end of the field and attempted, drunk as they were, to set up a tent.

In the morning, Beat and I had fun showing Urs the tire tracks in the grass, and then set off. We hadn’t walked far, however, before we realized that none of the cars that had driven by us would have had room for three young men. We decided to split up. Beat gave me his address in Switzerland, and I set visiting him as a goal. Perceptive readers will notice how circumstances and opportunities were chipping away at my original plan to spend my year in Paris.

It was Sunday morning. I had now been in Europe for a week, even if it has taken a month for me to recount the story.Labels: 1972, Anecdotes, Bilingualism, Europe, Language Acquisition, Memoir, Travel

Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #4

Thursday, September 29, 2022

After two days of walking the streets of London, I was ready to leave for Ireland. I figured I could do a quick loop, take a look around, return to Earl’s Court to pick up any mail, and then proceed to France to settle in. The London Underground rises above ground after it gets outside the central city, and took less than two hours to reach Oxford. I have a friend who is spending a week in Oxford at the moment, and I’m sure it will be productive time, but my goal was to reach Stratford-upon-Avon by nightfall. My one memory of Oxford is a wide grassy stretch beside the highway as I walked.

I realize that Oxford has one of the world’s fine universities, the oldest in the English-speaking world. (My youngest son would study his junior year abroad there). Oxford got its big boost in AD 1167, when my ancestor, Henry II, banned his subjects from attending the University of Paris. Of course Oxford had turned up often in biographies. Growing up in the Methodist Church, I knew about the ‘Holy Club,’ founded by Charles Wesley, led by his brother John, and including America’s first great evangelist, George Whitefield. Yet, by my late teens, I had left behind my Methodist upbringing, and could no longer claim the Wesleys as my own. Perhaps, as well, I was still burned out after my last year at UCLA. I had no strong desire to walk around another university.

I doubt that I walked the whole 39 miles from Oxford to Stratford, but I don’t recall hitching any rides. The town of Woodstock stands out, a medieval settlement that has guarded its historic appearance. I did not realize how close I was passing to Blenheim Palace—just a hundred yards off the highway—where Winston Churchill was born and where Queen Mary locked her half sister Elizabeth away. When I visited England in 2019, my main objective was time with kids and grandkids, but Blenheim was the next thing on the list of things I didn’t get to.

In Stratford, I found the Youth Hostel and checked in. Across Europe, I was to discover that the rural YHs were more attractive and less expensive than the city versions. They were mostly stately mansions that had been donated when a younger generation could not afford to pay the inheritance taxes. I seem to recall that a bed with mattress at most of the rural Hostels cost me about the equivalent of 80 cents U.S., and I was carrying my own sleeping bag. The bedrooms would have three or four sets of bunkbeds, and guests could use the kitchen, though no meals were provided. In the morning, I found the Royal Shakespeare Theater and bought a ticket for a play the following night.

After pushing for several days, Stratford allowed me to rest. I’m a sucker for the Tudor-style, black and white or black and tan, half-timbered buildings. In my mind’s eye, I have intended to build one for myself, though it gets ever-smaller as I age and my ambitions shrink. It fascinated me how buildings dating from the 1500s could now have indoor plumbing and neon lights.

I took some time for a peaceful hike, through fog, along the River Avon. I had much on my mind. The previous three months had raised the possibility that I had found my life partner. I met Vicki during my first quarter at UCLA. We had one class together, ‘Education of the Mexican-American Child.’ It would be the only education class I took there. I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to be a teacher, but with a History Major and English Minor, that could be a possibility. During my two years at UCLA, I tutored English to 4th grade immigrant kids in L.A. Chinatown. A year earlier, after deciding my years of competitive running were over, I went back to my high school coach, and he gave me the tenth-grade cross country team to try my hand with. We made it that year to the city finals. I’d enjoyed both of those teaching experiences.

At UCLA, though, I took a series of creative writing classes. A writing career interested me, but not if I needed to be ready to support a family. I knew too many starving writers. For a short time, I pondered studying for the pastorate. That would have been for all the wrong reasons, as much to figure out what I believed about God—if He existed—as to serve the God who might be there.

Then, on a lark, I took a Movement Behavior class, partly to better be able to describe my characters in fiction. The professor, Dr. Hunt, was teaching Kinesiology in the Dance Department, but as a physical therapist she had lived among and treated Bedouins, Inuit, and a variety of other cultures. She introduced a remarkable amount of anthropology. I was so blown away by what I learned that the following quarters I took every class she offered. In the process, I didn’t quite finish my minor in English, but I did complete one in Kinesiology. I began to ponder a career in Physical Therapy, until I realized I would need two years of math and science prerequisites before PT school. As I walked along the River Avon, I leaned toward teaching. Vicki was studying to be a teacher. Two teachers would have the same vacations.

At Thanksgiving of my first (junior) UCLA year, I mistook a reply from a young lady and incorrectly jumped to the conclusion that I was engaged. Between Thanksgiving and Christmas, I was checking my dorm mailbox multiple times each day, always to find it empty, but sometimes to see the student who was sorting the mail on the other side. I knew her slightly from my ‘Education of the Mexican-American Child’ class. On the first day of that class I did what all unattached students do, I glanced unobtrusively around the room, and thought to myself, “Nothing here.” She remembers whispering to Bonnie, her roommate, “Nothing here.”

They lived two floors above me and we often left for class at about the same time, so I occasionally walked them to the main campus, or saw them in the dorm cafeteria. At the end of the quarter, Tuesday of finals week was my 21st birthday, and I went home to celebrate with my parents and siblings. Back on campus, the next evening, a coed was stabbed to death in the parking structure not far from our dorm. The crime has been connected to the Zodiac Killer, and left the whole campus on edge. When the final exam for the education class got out after dark on Saturday evening, I finished early, but stuck around outside to walk the girls back to the dorm. I was still thinking about the girl from Thanksgiving, but I remember thinking that I hoped there was someone available to walk my future wife safely home. Little could I have imagined.

We had to move out of the dorm for the Christmas holidays. My parents came to help me transport my things, and while Dad and I made several trips up and down the elevator, my mother—who could strike up a conversation with anyone—chatted with the nice young woman who worked behind the desk, who seemed to know me.

I do not remember what play I saw at the Royal Shakespeare Theater that night. What fascinated me most was the way the set could be staged with almost no scenery. Instead, sections of the stage itself would rise or fall, high to become the bow of a ship, or less to become a bench. However, I could leave and say that I had seen a Shakespeare play at Stratford-upon-Avon. I walked back to the Youth Hostel ready to leave in the morning for Ireland. Admittedly, that was in the opposite direction from France.

Once, for a session of the Movement Behavior class, Dr. Hunt took the students to a large, walled-in, grassy area behind the Women’s Gym. Our assignment was to move. Just move. After a while, she called us in and she reported what she had seen. The class was heavily dance majors, and she’d observed the way many of the students had picked a spot and waved arms and legs or done a variety of artistic contortions. Then she got to me, and chuckled. “Brian, you explored every inch of grass and every corner.” I didn’t realize it yet, but that would describe my trip to Europe.

Labels: 1972, Anecdotes, Europe, History, Memoir, Teaching, The Writing Life, Theater, Travel, UCLA

TRUE BLUE: Reviewing a ten-year-old book

Sunday, July 29, 2012

A previous Dodger post, The Back of Duke Snyder's Head, is from Feb 28, 2011.

The link on this screen saver is here

Labels: Anecdotes, Baseball, Books, California, Colombia, Europe, Famous People, History, Lomalinda, Memoir, Sports, Travel

The Back of Duke Snider's Head

Monday, February 28, 2011

The report today of Duke Snider’s passing brings two small memories to mind, though most of his Hall-of-Fame career (1947-1964) was before my time and on the other side of the continent.

My Time with baseball started in 1959, the Dodgers’ second year out of Brooklyn. My Cub Scout den drove downtown to the Coliseum to watch the Dodgers host Cincinnati. I would have been nine, and I’m not even sure Snider played. I remember Pee Wee Reese, Wally Moon, and Gil Hodges. It was still the core of the team that had come from back east, and Snider was one of its most fabled players, but I hadn’t yet caught the fever. We sat in way-yonder center field seats where Snider would have been the nearest player in front of us, so maybe I spent nine innings staring at the back of his head. However, my two strongest memories are how far from the game we actually were, and how fast the Reds’ Vada Pinson could run from home to first on a single.

I didn’t really become a baseball fan until the Kaufax-Drysdale-Wills teams of the mid-60s. By then, the Dodgers had moved from the Coliseum to their own stadium, and Snider had moved to the Mets, Giants, and retirement. It was then I finally saw the Duke up close.

Off-season, Snider made his home in Fallbrook, California, rooted for the local high school athletic teams, farmed avocados, and attended the Methodist church. My own family had tried weekend avocado ranching near Fallbrook. My cousins attended high school there, and played baseball. They also attended the Methodist church, and I heard frequent mention of Duke Snider.

One Sunday, we made the trip to the Fallbrook church. My mother’s favorite, but long-retired pastor was making a guest appearance. As I took a seat, my cousin pointed at the man in front of me. “That’s Duke Snider,” he whispered. I spent the next hour looking at the back of the great man’s head. Afterwards, Snider got up and left and my mother pulled me up front to show me off to her pastor.

There you have it: a baseball great passes on to the ages and my two strongest memories are of the back of his head. Rest In Peace, Duke.

For another discussion of the Dodgers, go here.

Labels: Anecdotes, Baseball, California, Famous People, History, Memoir, Sports

A Civil Fred Korematsu Day, to You and Yours

Saturday, January 29, 2011

Tomorrow will be Fred Korematsu Day, as will January 30th in all future years, declared so by Governor Schwarzenegger and the unanimous desire of both houses of the California Legislature. Parallel days in Oregon or Washington might honor Minoru Yasui and Gordon Hirabayashi. In my own mind, it will be Jiro Morita Day, and by extension—like a Rosa Parks Day or a César Chavez Day—it will be a time to reflect on how citizens in a supposedly civil society can respond at those moments when civility is in jeopardy.

While I was growing up, each of my parents spoke of the pain and confusion they felt in 1942 when their Nisei classmates were sent away to government “Relocation Camps.” Later, while I was taking a year of Japanese language at Pasadena City College, the school offered “Sociology of the Asian in America.” The course might qualify among the ethnic studies courses that have just been outlawed by the state of Arizona, but I look back upon it as one of the most fruitful classes I ever took. Three hours one night a week, with a 20 minute break, I quickly began spending those twenty minutes—and the walk to the parking lot after class—with Jiro Morita. At 80, he told me he was taking the class “to stay young.”

I spent every possible moment asking about his long life.

In early 1942, when the United States government was preparing to lock up the entire Japanese community on the west coast, the Japanese themselves worked through intense debate over how to respond. Poet Amy Uyematsu, Mr. Morita’s granddaughter, writes,

Grandpa was good at persuading the others

after the official evacuation orders.

Detained at Tulare Assembly Center,

he was the voice of reason among his angry friends,

raising everyone’s spirits

when he started the morning exercise class.

(From “Desert Camouflage,” in Stone Bow Prayer)

Most of the issei (1st generation immigrants) and nisei (2nd generation/US citizens) decided that obedience to the government’s order would offer their best long-term hope for full integration into American society. Three American-born young men, however, decided to test their 14th Amendment rights and protections. Korematsu, Hirabayashi, and Yasui performed that most-American of exercises: they took it to court.

Korematsu (1919 – 2005), born in Oakland, first tried plastic surgery and a name change to evade the order for Japanese to report for relocation. When that failed, he agreed to let his arrest be used as a test case. Korematsu remained at the Topaz, Utah, internment camp while Korematsu v. United States worked its way to the Supreme Court. They decided against him, 6-3.

Although Korematsu was an unskilled laborer, both Hirabayashi (b. 1918, in Seattle) and Yasui (1916-1986, of Hood River) had earned bachelors degrees from their state universities. Yasui even held a law degree and the rank of second lieutenant in the U.S. Army's Infantry Reserve. The relocation order was preceded by curfews, which each man intentionally violated before surrendering to authorities. Eventually the Supreme Court linked the two cases and rendered a unanimous decision: The government had the authority to order detention and relocation of even U.S. citizens under its war powers. Korematsu’s conviction was not overturned until 1983, Yasui’s until 1986, and Hirabayashi’s until 1987.

Source

In the early 1970’s, I had a brief, chance meeting with Gordon Hirabayashi. During my two years at UCLA, I studied additional Japanese language and a year each of Japanese and Chinese history. I also volunteered as an ESL tutor at Castelar Elementary School (L.A. Chinatown), and as a summer counselor for an Asian session of Unicamp. This took me often into the Asian American Study Center, where Elsie Osajima, Mr. Morita’s daughter, was an administrative assistant. Once, when I entered Mrs. Osajima’s office on some errand, I found several people chatting with Mr. Hirabayashi. It was very like a similar meeting, during the same months, and no more than 500 yards apart, with former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Earl Warren. In each case, I knew it was a rare privilege to connect with an important moment in history, and yet the situation didn’t allow for me to ask questions. On the spur of the moment, I couldn’t even think of any.

However, the two meetings provide an interesting juxtaposition. Earl Warren, as Attorney General of California, was the driving force behind convincing President Roosevelt of the necessity for removing the Japanese from their homes and communities. The same Warren Court (1954-1969) that did so much to advance civil rights in so many other areas also could have been the court to reverse Korematsu, Hirabayashi, and Yasui. It didn’t. What my parents identified immediately as wrong when their high school chums were hauled away in 1942, the federal courts only caught up with in the 1980’s. Then, California recognition had to wait until 2011.

If there is a lesson in Earl Warren’s life, it is that for any community, prejudice is easiest to see from outside the area, or outside the era. Warren could see the prejudice against African Americans in the South, yet at the same time, he was either blind to, or unwilling to face prejudice against the Japanese in California. This brings us back to Arizona, today, and the efforts to redefine citizenship. Fred Korematsu looked back on his own case and pursued justice an a reversal of the court's decision, not for his own sake, but so that the United States could be counted on to give the 14th Amendment guarantees to every person ever born or naturalized in the United States, and in whichever state they might reside.

May it ever be so.

As I prepared this post, the miracle of Google allowed me to connect with Amy Uyematsu and Elsie Osajima. I intend soon to write more about Jiro Morita. He was an amazing man.

In the meantime, enjoy a civil Fred Korematsu Day. Pick an injustice, and ponder how to alleviate it.

http://www.amerasiajournal.org/blog/?p=1840

http://www.amerasiajournal.org/blog/?p=1840Additional Resources:

Korematsu v. United StatesHirabayashi v. United States

Yasui v. United States

Ex Parte Endo

In this PBS video, Mr. Korematsu tells his own story.

This book targets readers from 3rd to 6th grades.

This book targets grades 7 through 10. Although it appears to be out of print, used copies may be available. Perhaps, now that California has an annual Fred Korematsu Day, it will be reprinted.

Gordon Hirabayashi - On the Day of Remembrance: A Statement of Conscience

Gordon Hirabayashi - On the Day of Remembrance: A Statement of ConscienceIn this nearly-two-hour from 2000, Gordon Hirabayashi discusses the Japanese Evacuation and its importance to history.

Disclosure of Material Connection: The Amazon links above are “affiliate links.” This means if someone clicks on the link and purchases the item, I will receive a commission. This has never happened to me as of today, and would only be a pittance if it did. I have no financial arrangement concerning any of the other materials I have linked with. I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.”

Labels: Anecdotes, Bilingualism, California, Famous People, History, Immigration, Japan, Memoir, Milestones, UCLA

Right Place at the Right Time

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

God's Guest List: Welcoming Those Who Influence Our Lives

by Debbie Macomber

• Hardcover: 208 pages (also available for Kindle)

• Publisher: Howard Books (November 2, 2010)

• ISBN-10: 143910896X

It’s always fun to be anthologized. It means an author interested in a subject surveyed the available literature and found one’s offerings noteworthy. That kind of complement puts an extra zest into sitting down at the keyboard for one’s next efforts.

Debbie Macomber has had a career in fiction that proves the power of plodding. I heard her tell her own story at the Mount Hermon writer’s conference, where she was the keynote speaker in 2008. A dyslexic with only a high school education and toddlers to care for, she yearned to be a novelist. Macomber tells the story with humor, but what I took away concerned a tenacity that eventually paid off with over 150 novels published, and over 60 million copies sold. Within the industry, people also mention her stunning accomplishment in maintaining a mailing list with every person who ever expressed an interest in her writing (begun in a shoebox, before the advent of computers), and her use of that list for a steady output of thank-you notes and personal invitations anytime she would be appearing in an area or releasing a new book.

Macomber was fun to listen to, and some of her modules show up in this volume, one of her rare ventures into non-fiction. Of course, that’s not why I’m plugging her book on my blog. However, the explanation begins with that same 2008 conference at Mount Hermon. It's a right-place-at-the-right-time story about getting into an anthology of right-place-at-the-right-time stories. There, at a meal, I briefly met Janet Kobobel Grant, of the Books and Such Literary Agency.

After the conference, I put the agency blog, Between the Lines, on my reader. The agency’s members rotate the duties and host one of the better daily conversations about writing and the publishing industry. Over these 30 months, I have joined in when the topic brought something to my mind.

A writer is only a writer if he or she writes. My problem is that teaching junior high school is an extreme sport. After running 7:30 to 3:00 on adrenalin, trying to stay one step ahead of 120 teens, the kids leave and I go brain-dead and drowsy. Sometimes in the evening I write tests or worksheets. I don’t have the oomph to work on my novel. But a couple times a week I might have the energy to craft one good paragraph and leave it somewhere on a blog.

So when I returned to Mount Hermon for this year’s Christian Writers’ Conference, I made a point of searching out the Books and Such table at lunch the second day. Wendy Lawton was already seated and was asking people’s names. I gave her mine and her eyes dropped immediately to my name badge, “Oh,” she said, “I’ve been wanting to get in touch with you.”

For an unpublished author, that kind of opening line from a respected agent is about as good as it can get. But it got better. Wendy explained that she was working with Debbie Macomber on a book project and they wanted my permission to include an anecdote I had posted on their blog. It’s an account from my 2004 trip to China. I’d already reported a variation of it here, but it was a rich enough experience that it could be told from a dozen different angles, each supporting a different thesis. In this case, I offered it in response to comments Wendy had posted about literary pilgrimages.

The upshot is, this week’s mail brought a signed copy of Debbie Macomber’s new book, God’s Guest List: Welcoming Those Who Influence Our Lives. (I'm sure I've also made it onto her prodigious address list.) She asks the reader to look at those times in our lives when we were at the right place at the right time and to acknowledge that these weren’t coincidences. Some of this overlaps the keynote addresses she gave at Mount Hermon, other parts of it are new. Some of it is her own story. Some of it comes from others. And page 72 is all mine.

Before her career got off the ground, Macomber made a list of famous people she wanted to meet and began pecking away at it. However, as she began to actually meet some of these people she found herself disappointed. Up close, some of the famous turned out to be unimpressive or even unpleasant. That caused her to begin looking closer at the non-famous, the people all around her whom she had previously looked right past. Then she began to examine those "coincidental" moments that she had previously not focused on, and to gather similar experiences from others. From those examinations came this book.

Like any anthology, it can be read straight through, or in small doses. I’ll admit: I skimmed through until I found page 72. Now I’ve gone back and read some of the passages I skipped over, and others beyond. There’s some interesting stuff. It’s a book I can enjoy being a part of. I was at the right place at the right time, and I'm glad for it.

Labels: Anecdotes, Blogs, Books, Christian Worldview, Famous People, Memoir, Teaching, The Writing Life

A Little Memory of John Wooden

Saturday, June 05, 2010

Many people who knew John Wooden much better than I are recounting stories of him today, and I have no original pictures. But I can’t let his passing go completely unmentioned here. Wooden graduated to Heaven yesterday, at 99.

Many people who knew John Wooden much better than I are recounting stories of him today, and I have no original pictures. But I can’t let his passing go completely unmentioned here. Wooden graduated to Heaven yesterday, at 99.

The last time I saw John Wooden was spring of ’72. He came out a side door at Pauley Pavilion, just as I approached, and he gave me a little smile and nod of his head. It was the same door I’d seen Haile Selassie exit from four years earlier, but I’d gotten neither a smile nor a nod on that occasion. Selassie was the reigning emperor of Ethiopia. Wooden, the “Wizard of Westwood,” was the reigning king of college basketball. He’d just won the 8th of his eventual ten NCAA National Championships. At UCLA, his genius was more recognized than any of our Nobel Prize winners. If it had been his nature to be as imperial as Selassie, he had earned the right.

Wooden had given a guest lecture a few weeks earlier in one of my kinesiology classes, but I can’t imagine he still recognized me. I was just one of 35,000 students at UCLA., but more than anything else, Wooden was a teacher. All 35,000 of us were his students, and I got a smile.

I’ve read that after ten national championships he was most proud that his teams ranked highest in number of athletes who actually graduated. I became acquainted with some of those young men, Terry Schofield, Sven Nader, and Keith (later, Jamaal) Wilkes. He recruited athletes of fine character, not just physical prowess. Among his many personal accomplishments, he was proudest of winning the Big Ten Academic Achievement Award (during the year he also led his team to the conference championship) for the highest GPA. He was a remarkable man, a gentleman scholar, and a servant of God, and I was blessed by the little bit he touched my life.

(In poking around on the web, I find this interview with Wooden, in which he quotes a poem written by Sven Nader. Nader lived in our dorm during my sophomore year [as did Wilkes, Bill Walton, and the rest of the freshmen team]. I remember Sven's beautiful singing voice. Seven-footers have a lot of lung capacity.)

Labels: Anecdotes, California, Christian Worldview, Famous People, Milestones, Sports, Teaching, UCLA

Thanks, Lucho: tribute to a great teacher

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

Yesterday I attended the memorial service for Luis “Lucho” Figallo, long-time Spanish teacher at Golden West, the high school where four of my five children attended. All four studied under Mr. Figallo, probably averaging two years apiece. That’s eight Back-to-School Nights, eight Open Houses, and somehow, we always got around to see Mr. Figallo, even when we didn’t have kids in his classes. Oftentimes we stayed late in his classroom. After all the other parents had gone home, Lucho would offer advice to my fledgling-Spanish-teacher wife. He was always ready to give help, switching back-and-forth between beautiful Spanish and his own ebullient brand of English.

For most of the nearly 20 years I knew Lucho, he insisted that he was “going to retire in another two or three years,” but he only left the classroom two years ago. He was a people person. He loved his students. He loved his subject. After teaching high school all day, he taught night school at the local community college, often to classes full of his former students. I saw a post today on the College of Sequoias site, from a former student at both schools who then went back into Mr. Figallo’s Golden West class as a substitute teacher. “. . . even though he wasn't there in person his loving presence was felt. I don't know if it was because of all the kind smiles on the student faces or if it was because of that jolly old piñata with Figi's resemblance.”

I know the history of that piñata. A committee worked on it, but it took its final form in a back bedroom at my house. And it did bear an uncanny resemblance to Figallo. He was wearing a beard in those days, but it was that smile (and if I recall, the Panama hat) that gave it away.

Each of my children who had him has fond memories of Mr. Figallo, but my greatest debt goes back to the year my eldest son entered 9th grade. We were just back from five years in Colombia, but my son was very unsure of his Spanish. Under Mr. Figallo, I saw his confidence grow. Then, just before Easter, Figallo pulled Matthew aside. The youth group from the church where Lucho was an elder needed a translator for their Spring Break trip to Mexico. Would Matthew consider helping out?

Matthew went. He was one of the youngest members of the group and had not been part of any of the team-building exercises or fund-raisers. However, as the translator, Matthew found himself where the action was, in a key position of leadership. He came home secure in his Spanish and suddenly aware of new gifts as a leader. But it did not stop there. Lucho continued to support and encourage Matthew through another decade and a half. The confidence Matthew gained studying under Mr. Figallo has carried him into fluency in German, Russian, and Portuguese and starts in a couple more. Thanks, Lucho.

Lucho grew up in Peru and came by himself to the US as a young man, learned English while working in a grocery store, and earned a masters degree in Spanish Literature. A coworker gave him a Bible. He studied it carefully and decided to base his life on what he found there. At the end of his life, battling cancer, he and his wife prayed that God would give him the strength to make one last trip to Peru, to say goodbye to the family he left behind, and to encourage their Christian walks. Coming back into Los Angeles, when the pilot announced “We are now beginning our descent,” Lucho said only, “I’m not going down. I’m going up.” With that, he stood in the presence of Jesus.

A life well lived.

Thanks, Lucho. I hope Mary has the piñata.

Labels: Anecdotes, Bible, Bilingualism, California, Christian Worldview, Immigration, Language Acquisition, Milestones, Teaching, Visalia

My Hat, It Has Three Cognates

Tuesday, January 06, 2009

Natu found me eating breakfast in my stockinged feet and brought one of my big shoes, lifted my foot to maneuver it into place, and then ran off to get the matching partner. Pretty ambitious for a 28-month-old. Once my shoes were on, he went to the front door and stood beckoning. We located his shoes and a sweatshirt, and I put on my hat. Natu raced off to find his chapéu. His Portuguese-challenged grandfather defaulted to the chapeau of other-wise forgotten high-school French, which his grandmother corrected and sent us on our way. With chapéu, there is no conflict between Natu's Portuguese and the sombrero of my wife’s Spanish, and only a rough resemblance to her Italian cappello. As we race to keep up with our bilingual grandson’s Portuguese, it intrigues me that when the Portuguese varies from the Spanish, its cognates sometimes run after the French, and other times bow to the Italian.

Photo by Natu's Grandma

On our walk, Natu and I saw an “avião up in the sky!” (Which I heard as the Spanish avión, and no doubt confused him as I repeated it.)

He gets excited by the Christmas lights that are still up and is working hard on his colors. He nails yellow pretty consistently, but confuses blue, red, and green. Of course, with his mother they are azul, vermelho, e verde.

Over our heads, it was “Squirrels dançando!” while at our feet it was “Pinecones swimming!”

We stooped and I introduced him to water-logged acorns. He took one in each hand, “One acorn! Two acorn!” The numbers are also coming in both languages. I showed him how acorns have chapéu. He met that with the glee that only a two-year-old can muster.

“Acorn, chapéu!” we volleyed back and forth.

Natu and Papa both understand the first rule of language learning: ‘Put every new word to immediate use.’

Labels: Anecdotes, Bilingualism, Grandparenting, Language Acquisition, Linguistics