Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #2

Saturday, September 17, 2022

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

I had an address for a bed and breakfast in Earl’s Court, a mere 32 miles away. I had walked that far in a day previously so even after I realized my mistake, I was not concerned. I had hiked the high Sierras. I ran run cross country in high school and my first year of college. I’d run a marathon in Mexico. I once got my high school class to challenge the class just ahead of us to a contest to see which class could rack up the most total laps on a Saturday, and personally tallied 33 miles, so I set out on a beautiful sunny morning to walk to Earl’s Court. I probably walked past dozens of bed and breakfasts that would have served me well, but a friend had given me the address of the place he’d stayed in Earl’s Court.

First time travelers may be struck by the fact that a foreign country appears in the same colors as at home, but somehow looks different. I was pondering that when a car stopped and a young man offered me a ride. I gladly accepted, and obeyed his instructions to stow my rucksack in the boot. Do you know that the British drive on the wrong side of the road? They also seat the driver on the wrong side of the car. I had read about it, but now I saw this peculiarity verified.

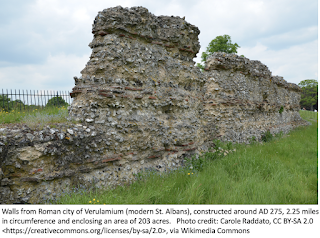

When my benefactor learned that this was my first day in England, he decided to divert and show me some local Roman ruins. We had a most congenial time, and then he let me out to continue on my way. The countryside gradually gave way to industrial areas, and then brownstone residential areas, and then I was in Earl’s Court. I had successfully flown across an ocean, walked most of 32 miles, gotten some exercise (though not much to eat), met a native, seen some Roman ruins, and located a target address. I decided I ought to recount my safety and my successes in letters to Vicki and my parents.

Of course, I had no return address to offer them other than the bed and breakfast in Earl’s Court, and it would be two weeks for my letters to get to California and receive answers back (Note to those who grew up in the age of email and texting: Letters were a thing that allowed Neanderthals to communicate over long distances, albeit very slowly). On the plus side, those two weeks would allow me time to visit Ireland before continuing to France, where I would hunker down with my novel and the French language. I still entertained that objective.

A few thoughts from 50 years later:

After yesterday’s episode, I messaged with a high school friend who did her travel with the army, as a nurse, and though she did not go to Vietnam, the topic came up in our discussion. For my generation, it often will. For my cohort, our post-high-school years were either spent in Vietnam or trying to stay out of Vietnam, or maybe protesting in the streets over Vietnam.

Like many of my peers, I was conflicted about Vietnam. I loved my country and wanted to defend it, but questions nagged me about whether in Vietnam we were the good guys or the bad guys. I started college three days after high school, not because I wanted to avoid the draft (Note to those who grew up in the era of an all-volunteer army: It used to be that when the letter from the draft board arrived, you reported for military duty). In 1968, the best way to stay free of the draft was to stay in school. Although I did want to avoid the draft, my primary motivation for college was excitement about college. However, those first weeks, I buddied around with a friend who really wasn’t that excited about school. Toby dropped out, got drafted, and died standing in the boot camp breakfast line. A recruit standing behind him dropped his rifle.

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

The spring I was finishing up at community college and getting ready to transfer to UCLA, the employment office connected me with a middle aged veteran who needed a man Friday. Pat suffered from emphysema, due to an accident in the Air Force. He knew he was dying, and wanted to do so in Europe. My job would be to carry his oxygen tank, and then accompany his body home at the end. He would pay all of my expenses and a nice salary. Most importantly for me, it would be my longed-for trip overseas. I look back on that episode as the supreme test of my transition to adulthood. Going with Pat would mean I would have to cancel my plans for UCLA. Pat told me Sen. Cranston owed him some favors and could fix me up with the draft board. Although I didn’t want to go to Vietnam, I also didn’t want some politician pulling strings for me. I drove Pat to Cranston’s office, but the Senator had been called away that day. Pat was expecting a big check from the government, but I began to wonder if it was actually coming. Pat liked to brag about the friends he looked forward to seeing, but from his description, some of them impressed me as a little shady. He also talked about the girls he would be able to get me, and how they could move in with us. That wasn’t the kind of girlfriend I wanted. After investing five or six months in Pat’s dream, and as much as I wanted to see Europe, I realized that I wanted to be my own boss when I traveled. I told Pat I was going to UCLA. To have gone with Pat then would have traded away everything of value that I have today.

I remained timid and indecisive about the war. I took part in a few demonstrations, and wavered over the question of what to do if drafted. I could not imagine killing another human being. Maybe I would go in as a medic. Maybe I would go to Canada. Dying for my country was one thing, but what if our side was actually the bad guys? That would be worse than dying in the boot camp breakfast line.

One more friendship stands out: I had written a 500 page—typed, double spaced—murder mystery (Note to those who learned word processing at a computer key board: Word-working was once done at a manual instrument that left one’s fingers raw and swollen at the end of the writing day). I had alternated 12-hour writing days with days carting Pat around. UCLA had a novel writing contest that first quarter and my 500 pages lost to a Vietnam vet’s 30-page opening chapter. Brian Jones took his $5,000 prize, went home and beat up his wife. The prize went for her hospital costs and the divorce. Over the next two years that I had to get to know him, I watched the Man Who Had Everything slowly fall apart.

We did not understand PTSD in those days, nor PITS (Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress), a concept first described by Psychologist and Sociologist Rachel MacNair. As I heard MacNair present at a conference in 2019, and then driving the carpool back to our shared AirB&B, she put into words exactly what I sensed had happened to Brian Jones. Brian had been the All-American everything: football quarterback, Student Body President, going steady with the head cheer-leader. Then he had done the All-American thing to do in 1966; he joined the Marines. When I asked about his experience in Vietnam, he could only shrug and say, “I killed a lot of Gooks.” There is PTSD trauma that soldiers experience when bullets are flying and friends all around them are dying, but PITS kicks in when someone raised with high moral values must face that they have become a murderer. Within a few months of my return from Europe, Brian Jones drove a van full of marijuana over a cliff, while running from police.

I believe I have seen PITS twice more. For a while I was visiting and corresponding with an inmate on Death Row in San Quentin Prison. He had been convicted as a serial killer. Independent research brought me an account of a childhood murder-dismemberment (of his mother) in which he had been forced to participate. Every one of his murders had been a reenactment of that event.

And then, in helping a friend clean up after a tenant, I found the letter-to-herself of a woman whose life had spiraled down after an abortion. Her agony came out in one haunting line, “This is not who I am!”

In 1972, as I left for Europe, the United States was struggling with a similar disconnect. “This is not who we are!”

Labels: 1972, Abortion, Aviation, Europe, Friday 10:03, History, Memoir, Milestones, The Writing Life, Travel, UCLA

Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #1

Friday, September 16, 2022

Fifty years ago, today, I boarded a flight in Los Angeles and flew to Luton, just north of London, UK. Thus began the great coming-of-age adventure of my life. My mother and my then girlfriend (Vicki, who has now been my wife for 49 years) saw me off at the airport. In flight, I remember the Rocky Mountains covered with a layer of golden-yellow Aspen trees, ice chunks floating in Hudson Bay, an hour in a duty-free shop beside a snow-cleared runway in Iceland, and the first rays of daylight as we took off from Edinburgh. I was 22, and—unlike today—I had been able to work my way through UCLA with no debts, and graduate with $1,000 in the bank.

I did not walk in the graduation ceremonies. Skipping those expenses gave me another hundred dollars for my voyage. Instead, I walked from my last final exam to a student travel agency and bought my one-way ticket to Europe. The other choice had been Japan, which interested me more, but five years of French would serve me better than my three quarters of Japanese. It was my plan to sojourn for a year in Paris. I would work on making my French useful, and write on the novel from which I had already shown Vicki portions over a year earlier. My last quarter at UCLA had been exhausting. During registration, a counselor pointed out that I had accrued 207 units, and once I went over 208 without graduating, I would not be allowed to register for another quarter. I had transferred in from community college with more than the usual totals, and then decided to add a kinesiology minor and creative writing classes to my history major. I also, wanting to explore what eventually became my career, took the ‘Education of the Mexican-American Child’ class in which I met Vicki. The gist of it was, to complete all my graduation requirements, I needed to take and pass 28 units my final quarter. I may have set the all-time UCLA record for most units to earn a BA. As I returned to campus after buying my ticket, I looked out on the sea of peers who were practicing for the ceremony. Was there even one person I needed to say 'goodbye' to? Vicki came to mind. Our almost-two-year relationship had been friendly, but not romantic, and I did not see much chance that I could find her in the crowd. I did see her roommate, who promised she would pass along my goodbye. My main activity for the summer would be two volunteer sessions as a camp counselor, one with teen diabetics and the second for kids who came largely from Los Angeles Chinatown, where I had been tutoring English during my time at UCLA. One preparatory task for that was interviewing the families for each camper. One of those families spoke only Spanish. I had not yet begun the Spanish which would later serve as my almost-competent second language, so I called Vicki and asked if she would translate for me. On a Saturday morning I picked her up and we drove to Chinatown, but the family was not at home. I knew there was an Asian-American culture fair going on that weekend at nearby Echo Park, so we went there to kill some time. The family still wasn’t home, so we drove to USC, where Vicki would be taking classes for a teaching credential. We did a lot of talking. By the time I got her home in the late afternoon (unbeknownst to me, she had a date she needed to get ready for), I had begun to rethink our relationship. We had a wild summer. By the time Vicki and my Mom dropped me off at LAX, I was much less sure that I wanted to be gone for the full year. As we parted, I whispered, “I’ll be home for Christmas.”Labels: Aviation, Europe, Friday 10:03, Language Acquisition, Light at the End of the Tunnel, Memoir, Milestones, Teaching, The Writing Life, Travel, UCLA

DC-3 Nostalgia Follow-Up

Monday, January 24, 2011

Last month’s Capers tribute to the DC-3 became part of a conversation, both here and on Facebook, that included several of my former students and a couple of students who graduated from Lomalinda before my time.

Garth Harms obtained this picture from photographer Jeff Evans, who spent a couple of months in Colombia just before I got there. That dates the picture to late ’83 or early ’84.

Photo by Jeff Evans

It’s authentic, right down to the left-wheel and rear-wheel ruts where the plane pivoted to put its passenger door facing the covered waiting area. The entire community was here to receive my family when we stepped off the plane the first time, and in turn, we joined the crowd for countless welcomings and goodbyes. Departures had a ritual: after final hugs, the doors closed but the waving continued. Then the engines would rev (first one side, then the other) and well wishers would jump on motor cycles for a race to the last hill at the end of the runway, for final salutes as the gooney bird lifted off. This airplane was central to so many emotional moments that just looking at the picture—all these years later—touches a nerve.

One educational advantage that students in Lomalinda enjoyed was an unusual opportunity for work experience during high school. Kirk Garreans tells me he had the privilege of working alongside the DC-3 crew. Through his connections, he also came up with the fact that DC-3s continue to be active in the relief efforts in Haiti. Ponder that a moment: the youngest DC-3s are 65 years old, and still play a role in work-a-day aviation. Amazing.

Kirk also traced “our” DC-3 to its current owners, Dynamic Aviation, of Bridgewater, Virginia. The firm supplies “special-mission aviation solutions,” with over 150 aircraft doing commercial charter, fire management, sterile insect application, airborne data acquisition and other tasks. Before writing my first post, I was 90% certain I’d found the airplane, but Kirk’s information locked it. Dynamic Aviation restored the craft (N47E) to its original, 1943, Air Force paint job and insignia, and renamed it “Miss Virginia.” Here it is:

Finally, Kirk reported that Miss Virginia was part of the twenty-six plane, 75th Anniversary Fly-In to Oshkosh. Several nice videos are posted on You-Tube. Here is one:

A tip of the wings to all who participated in this conversation.

(My earlier post is here.)

Labels: Aviation, Colombia, Facebook, Former Students, History, Lomalinda, Memoir, Milestones, Photography, Product Reviews, Travel

Happy Birthday, DC-3

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

In the rush of Christmas, I’m a little late with this post. I had hoped to have it ready for December 17th, when one old friend turned 75 and another turned 108.

On December 17, 1935, at Santa Monica, California, test pilots tried out the first DC-3. Exactly 32 years earlier, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, Orville and Wilber Wright piloted their Wright Flier 1 to what is generally considered the first sustained flight by a self-propelled and pilot-controlled aircraft.

I’m not a pilot, but I enjoy being a passenger. I love both the arriving in some exotic place and—under most conditions—the process of getting there. Maps fascinate me, as does the world they represent. (Ask the two generations of students to whom I have assigned map learning.) Having the earth stretched out beneath me is like enjoying the map in its purest form. I have pressed my nose to the window of multiple crossings of the Atlantic, the Pacific, and the Caribbean, and on flights that puddle-jumped across four continents.

I remember all the places I visited, but some of those airplanes I got on, got off, and forgot. By far, my favorite flights were in the airplanes that carried me during the nine years I lived in Colombia. In 1984, I moved my family to Lomalinda, a small Bible-translation and linguistics center on the Colombian llanos, or eastern plains. When I arrived, the center had three single-engine, Short Take-Off and Landing (STOL) Helio Couriers, and an unusual looking plane called the Evangel. In addition, twice a week, the community was served by a DC-3 flight from Bogotá. Primarily, the small planes connected us to the state capital (Villavicencio, a.k.a. “Villao”), or remote areas where indigenous languages were still spoken. Through Bogotá, the DC-3 connected us to the rest of the world. Loading the DC-3, Bogotá, Colombia, October 1985

Loading the DC-3, Bogotá, Colombia, October 1985

Lomalinda was 35 miles from the closest paved highway, miles that were always difficult and sometimes impassable. I remember one rainy trip where buses and trucks lined up on both sides of a thousand-yard mud pit while two Caterpillar tractors sloshed back and forth, towing a single vehicle each trip. In good weather, the road trip to Bogotá took 12 hours. The DC-3 could do it in just under an hour.

Cockpit of the DC-3, with seats for pilot,

co-pilot, a third crew-member, and to

offer one passenger a remarkable

vicarious experience.

When the DC-3 went into production in the mid 1930’s, it revolutionized passenger airline service. It cut the New York to Los Angeles trip from 38 ½ hours (beginning with a train ride from N.Y. City to Cleveland, and then 13 more stops to L.A.), to 17 ¾ hours, with just three stops. In four years, as one airline after another went to DC-3s, the rate of passenger fatalities per million miles flown fell by four-fifths. Over the same years, the cost of airline tickets fell by half and the volume of passengers more than quintupled. DC-3s had captured 90% of the world’s airline traffic. By the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Douglas Company had built 507 of the DC-3s. War brought a military version, the C-47, and production that reached 4,878 in 1944 alone.

The DC-3 assembly line shut down in 1945. That means the airplane that carried my family that last leg to Lomalinda could not have been less than 39 years old. It might have been closer to 48. By comparison, I was 35. Before we left California, we junked the Dodge Dart we’d been driving. It died at 19.

It is difficult to pick a date in automotive history as dramatic as Kitty Hawk, but by 1903, motorcars had almost a century of experimentation behind them and were in production in both Europe and the United States. Still, by 1984, most pre-1945 models saved their public appearances for car shows. Few pre-’45 buses had regular runs and few pre-’45 trucks hauled freight. The DC-3 arrived 32 years into aviation history, and then served widely for roughly 50. This would be like the common-place usage today of a 1940’s telephone, or a 1980 photocopier.

My daughter, earning

her wings as a stewardess.

After World War II, cheap military surplus DC-3s made possible the beginnings of many new airlines, or fell into private hands. From Lomalinda, it was 35 miles in one direction and 60 in the other to find airstrips capable of handling a DC-3. Therefore, when storms sealed off either destination, airplanes landed on our strip to wait out the weather. I remember once counting 13 aircraft crowded in our little parking lot, half of them DC-3s.

In many ways, the DC-3, at age 50, was more comfortable than airplanes fresh off the assembly line today. For one thing, seats seemed roomier, aisles wider, and windows larger. True, the cabins were noisier, and unpressurized. At high altitudes (like over the Andes, to reach Bogotá), passengers sipped oxygen from tubes. I remember one painful flight with a head cold, descending into Lomalinda with the pilot circling the airport an extra two times to give my ears additional time to adjust. But more, I remember the spectacular views of Andes and Llanos.

Sipping oxygen at 16,000 feet

Colombians pass down a story that when God created Colombia, the angels came to complain that no place should be allowed such beauty. God is supposed to have replied, “Yes, but wait until you see what else I will do to it.” In many ways the country has suffered a torturous history, but its landscapes are breath-taking, and to fly over it is dazzling. Few places on earth display as many shades of green, or as wide a variety of clouds, sunsets, or rainbows.

The Colombian Llanos,

under the wing of the DC-3.

I might have ridden the DC-3 eight or ten times. It brought my youngest son home after his birth, brought my in-laws for a visit, and carried my wife and me to a second honeymoon in Bogotá. For part of one flight, I sat in the cockpit’s fourth seat and the pilot pointed out the unremarkable peak of Nevado del Ruiz. On November 13, 1985, a small eruption of the volcano melted the snowcap and sent a wave of boiling mud across the town of Armero, killing some 23,000 in the worst recorded lahar in history. The disaster sent our DC-3 into full-time relief service. Even at fifty, this veteran was not an air-show classic. It was still a workhorse.

For this reason, it came as a shock when the government decided no longer to allow DC-3s over the Andes. Ours had superchargers on the engines that gave them extra power and safety, and our pilots trooped to government offices looking for an exemption, but to no avail. Unable to use it for the Bogotá run, we had no choice but to sell it. My last photographs of the DC-3 are from 1987. I was told the plane had been purchased by a company that flew tourists over the Grand Canyon. It continued to serve.

This year, aficionados celebrated the DC-3’s three-quarters of a century with a formation flight across Wisconsin. Twenty-three DC-3s landed together in Oshkosh; of 26 that had had gathered at Rock Falls, Illinois, to attempt the flight; of the hundred or so still operational in the United States; of the some fifteen thousand made during the decade of their construction. Would you like one? I see this one advertised for only $299,000.

I found some of my history for this here.

Labels: Aviation, Colombia, History, Lomalinda, Memoir, Milestones, Product Reviews, Travel