Japanese Landscapes @ the Clark

Thursday, December 20, 2012

We arrived just a few minutes past 1:00 pm on Saturday, just a little late to catch the beginning of the weekly docent tour. Our three doubled the audience to six as Sonja Simonis, curator of this exhibit, talked about the individual artists, the 29 landscapes on display, and the represented traditions and influences, especially as the Japanese adapted what they learned from the Chinese. The Clark Center invites young scholars for assistant curatorial internships, and Simonis is the 18th intern in thirteen years. She told me she did most of her studies in Berlin, but researched her thesis in Japan.

The collection goes back into the 15th Century, and some of the commentary refers back to about the 10th. Several traditions are represented: Zen priests who painted as a path to enlightenment; Daoists who painted as a path back to nature and tranquility; bunjin, or literati, men of letters who painted as a pastime and to share with their friends; and professional painters who decorated castles for the Shoguns and Daimyo.

One of the oldest pieces, Mountains by a River, is attributed to Kenkō Shōkei (active about 1478-1506), a Zen priest who studied paintings from Song and Yuan China. In the Zen tradition, landscape paintings—usually of fictitious locations—served as meditative devises.

|

| Detail from Mountains by a River, a matching pair of hanging scrolls, attributed to Kenkō Shōkei. Ink and color on paper. |

|

| Winter Landscape (above), with detail (below), by Kanō Tan’yū (1602-1674). |

,+Priest+Looking+out+into+a+Snow-covered+Landscape.JPG) |

| Itaya Keishū (1729-1797), Priest Looking out into a Snow-covered Landscape, hanging scroll, colors on silk. |

|

| Detail from, Priest Looking out into a Snow-covered Landscape. |

When I looked closely at Landscape after Dong Yuan, by Nakabayashi Chikutō (who predates the opening of Japan), I was struck by its near-Pointillism, a technique I associate with late 19th Century, European Impressionists.

|

| Landscape after Dong Yuan, by Nakabayashi Chikutō (1776-1853). |

Nakabayashi served as a Nanga theorist, painting and writing in Kyoto.

Mizuta Chikuho (1883-1958) taught painting and frequently served as a judge in art exhibitions. In Fairly Unsettled Weather (1928), a figure in a blue kimono looks out from the window, the painting’s only deviation from a shades-of-gray color scheme.

|

| Fairly Unsettled Weather (1928), with detail at right, by Mizuta Chikuho. Ink and light colors on paper. |

|

| Plum Blossom Library (1926), with detail at left, by Fukuda Kodōjin (1865-1944). Ink and colors on silk. |

Spring breezes fluttering the lapels of my robe.

With just this peace my desire is fulfilled, while the world’s affairs leave me at odds.

White haired but not yet passed on,

These green mountains a good place to take my bones.

Who understands that this happiness today lies simply in tranquility of life?

(trans. Jonathan Chaves)

Color and detail also attracted me to Komuro Suiun’s Mount Hōrai. A contemporary of Kodojin, and another Daoist painter of the Nanga School, this painting pictures the palace of the Daoist Eight Immortals, who live in a place without pain or sorrow. Near the inscription, a flock of crains symbolize luck and long life.

|

Mount Hōrai, with detail on right, by Komuro Suiun (1874-1945). |

|

| Twenty-four feet from the 72-foot long of Hekiba Village, by Araki Minol. |

|

| Detail from Hekiba Village, by Araki Minol. |

In this video, I attempt to catch the sweep of Hekiba Village.

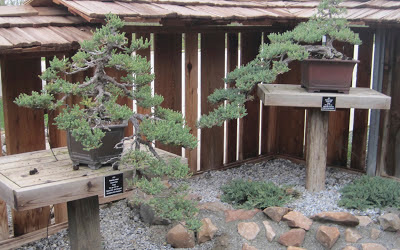

One final thought: Beside the art gallery, the Clark Center has a bonsai garden, and this has recently been redesigned to better show-off the collection.

(My review of a previous exhibition at the Clark)

3 comments:

Steve

said...

December 20, 2012 at 12:39 PM

Steve, this Saturday is the last day of the current exhibition. Then they will be closed to set up the new one, which will open on the 6th. If you want to be part of the opening day lecture, you'll need to call ahead for reservations. Which reminds me, I need to do that.

Brian

said...

December 20, 2012 at 2:44 PM

Those are wonderful work of art! - www.metropolitanpainting.com

Anonymous

said...

December 20, 2012 at 6:38 PM

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

+Hekiba+Village+.JPG)

Thank you for the reminder of the Clark. I've always wanted to go and maybe between your post and the Christmas break I may go.