Japanese Landscapes @ the Clark

Thursday, December 20, 2012

We arrived just a few minutes past 1:00 pm on Saturday, just a little late to catch the beginning of the weekly docent tour. Our three doubled the audience to six as Sonja Simonis, curator of this exhibit, talked about the individual artists, the 29 landscapes on display, and the represented traditions and influences, especially as the Japanese adapted what they learned from the Chinese. The Clark Center invites young scholars for assistant curatorial internships, and Simonis is the 18th intern in thirteen years. She told me she did most of her studies in Berlin, but researched her thesis in Japan.

The collection goes back into the 15th Century, and some of the commentary refers back to about the 10th. Several traditions are represented: Zen priests who painted as a path to enlightenment; Daoists who painted as a path back to nature and tranquility; bunjin, or literati, men of letters who painted as a pastime and to share with their friends; and professional painters who decorated castles for the Shoguns and Daimyo.

One of the oldest pieces, Mountains by a River, is attributed to Kenkō Shōkei (active about 1478-1506), a Zen priest who studied paintings from Song and Yuan China. In the Zen tradition, landscape paintings—usually of fictitious locations—served as meditative devises.

|

| Detail from Mountains by a River, a matching pair of hanging scrolls, attributed to Kenkō Shōkei. Ink and color on paper. |

|

| Winter Landscape (above), with detail (below), by Kanō Tan’yū (1602-1674). |

,+Priest+Looking+out+into+a+Snow-covered+Landscape.JPG) |

| Itaya Keishū (1729-1797), Priest Looking out into a Snow-covered Landscape, hanging scroll, colors on silk. |

|

| Detail from, Priest Looking out into a Snow-covered Landscape. |

When I looked closely at Landscape after Dong Yuan, by Nakabayashi Chikutō (who predates the opening of Japan), I was struck by its near-Pointillism, a technique I associate with late 19th Century, European Impressionists.

|

| Landscape after Dong Yuan, by Nakabayashi Chikutō (1776-1853). |

Nakabayashi served as a Nanga theorist, painting and writing in Kyoto.

Mizuta Chikuho (1883-1958) taught painting and frequently served as a judge in art exhibitions. In Fairly Unsettled Weather (1928), a figure in a blue kimono looks out from the window, the painting’s only deviation from a shades-of-gray color scheme.

|

| Fairly Unsettled Weather (1928), with detail at right, by Mizuta Chikuho. Ink and light colors on paper. |

|

| Plum Blossom Library (1926), with detail at left, by Fukuda Kodōjin (1865-1944). Ink and colors on silk. |

Spring breezes fluttering the lapels of my robe.

With just this peace my desire is fulfilled, while the world’s affairs leave me at odds.

White haired but not yet passed on,

These green mountains a good place to take my bones.

Who understands that this happiness today lies simply in tranquility of life?

(trans. Jonathan Chaves)

Color and detail also attracted me to Komuro Suiun’s Mount Hōrai. A contemporary of Kodojin, and another Daoist painter of the Nanga School, this painting pictures the palace of the Daoist Eight Immortals, who live in a place without pain or sorrow. Near the inscription, a flock of crains symbolize luck and long life.

|

Mount Hōrai, with detail on right, by Komuro Suiun (1874-1945). |

|

| Twenty-four feet from the 72-foot long of Hekiba Village, by Araki Minol. |

|

| Detail from Hekiba Village, by Araki Minol. |

In this video, I attempt to catch the sweep of Hekiba Village.

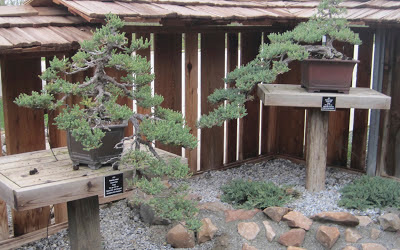

One final thought: Beside the art gallery, the Clark Center has a bonsai garden, and this has recently been redesigned to better show-off the collection.

(My review of a previous exhibition at the Clark)

Posted by

Brian

at

10:56 AM

3

comments

Labels: California, China, Garden, History, Japan, Museums, Travel

Lamentation of a Parent, Grandparent, and Teacher

Saturday, December 15, 2012

I took this picture during a school lockdown in 1994. In Colombia, unidentified soldiers had stepped out of the jungle within a mile of the school, so we locked down until we could be sure for whom those soldiers fought. My junior high students sat for two hours before the all-clear, joking nervously and missing lunch. But we were in a war zone. There, one understands—at least intellectually—that violence is a possibility.

In California, I once locked down with 4th graders while a funnel cloud just missed us. Before terrified ten-year-olds, the teacher must be strong, even casual about the situation, and compartmentalized. But now, even during our school’s annual lockdown drill, I have to stop and consciously gain control over the catch in my voice.

So it is good that I first saw news of the Sandy Hook shooting while I was alone in my classroom during lunch. As a teacher, a parent, and a grandparent, I cried. Then I compartmentalized, taught my afternoon classes, and went home to let my four and six-year old grandsons present me with an early-birthday batch of raisin cookies. Today, I will celebrate that 63rd birthday with a museum trip, and intellectualize.

The violence is common enough—even in elementary schools and movie theaters—that we have rituals for dealing with it.

One group of us divides into Pro-Gun and Anti-Gun factions. That is a debate we ought to have, though probably less driven by the most immediate atrocity. Prudence and self-defense may require that some citizens keep guns, but from scripture I draw the principle that trust in weapons is misplaced (Isaiah 31:1 and 2:7), and the glorification of weapons is idolatry. I waver over where to draw the legal lines on guns, but as a nation we trust and glorify them,. For trusting and glorifying, the lines should be at zero.

Another group points to lack of mental health, to the breakdown of the family, to a culture of violent video games, and to hopeless poverty. Yes, yes, yes, and yes. Every year I see students who are in need of better help than the schools are equipped to handle. I see boys—especially—trying to understand manhood when they have no fathers with whom to relate. This very week, I had several boys excited to show me videos that glorified lone attackers who vanquished large armies. I also just heard the verdict on a shooting a few years ago in the park around the corner from where I live. A lone gunman sprayed bullets into a pick-up soccer game, wounding one player. Charged with 10 counts of attempted murder, he received 500-years-to-life. The shooter was 16. Fatherless. Without a DREAM Act, he was also a boy without a country, and no hope of ever belonging anywhere. Except to a street gang.

Yet, curiously, the shooters in mass killings like that at Sandy Hook or in Aurora have been mostly white, middle class, and American born; as have been their victims. The other kind of shootings, kids killed one or two at a time as some gang initiate tries to prove his mettle, probably claim more victims in total, but make fewer headlines. The spontaneous monument in the photograph below sprang up after three boys were attacked in a yard across the street from where I pick up kids for Sunday school. One seventeen-year-old died. He had been a friend of the kids I pick up. The young shooter, who received a life sentence, was a recent alumnus of the school where I teach. Easy guns. Video games that glorify the lone shooter. Hopelessness and lack of belonging. Spiritual deadness. Isolated, one from this list does not create shooters, but together, they will.

So to cope with this, we compartmentalize. We intellectualize. We blame-shift. We look the other way that our drones are killing children in Afghanistan and Pakistan. We try and hide the fact that, each year, a million American children are denied even a day of birth. We flee from the knowledge that the stores we frequent support firetrap-sweatshops in Asia or Latin America, and that the chocolate we eat was harvested by child slaves in Africa. We have met the evil, and it is us.

Psychically we cannot carry these burdens, individually, or as a people. It is too heavy. We try to imagine ourselves standing in the way of all this, correcting it, or even absolving ourselves of our complicity in any of this, and we can’t. It is too overwhelming.

But it is not too heavy for God.

And God hears our cries.

I am driven this morning to read Daniel 9:4-19, and to use his prayer as my model.

4 I prayed to the Lord my God and confessed and said, “Alas, O Lord, the great and awesome God, who keeps His covenant and lovingkindness for those who love Him and keep His commandments, 5 we have sinned, committed iniquity, acted wickedly and rebelled, even turning aside from Your commandments and ordinances. 6 Moreover, we have not listened to Your servants the prophets, who spoke in Your name to our kings, our princes, our fathers and all the people of the land.

7 “Righteousness belongs to You, O Lord, but to us open shame, as it is this day—to the men of Judah, the inhabitants of Jerusalem and all Israel, those who are nearby and those who are far away in all the countries to which You have driven them, because of their unfaithful deeds which they have committed against You. 8 Open shame belongs to us, O Lord, to our kings, our princes and our fathers, because we have sinned against You. 9 To the Lord our God belong compassion and forgiveness, for we have rebelled against Him; 10 nor have we obeyed the voice of the Lord our God, to walk in His teachings which He set before us through His servants the prophets. 11 Indeed all Israel has transgressed Your law and turned aside, not obeying Your voice; so the curse has been poured out on us, along with the oath which is written in the law of Moses the servant of God, for we have sinned against Him. 12 Thus He has confirmed His words which He had spoken against us and against our rulers who ruled us, to bring on us great calamity; for under the whole heaven there has not been done anything like what was done to Jerusalem. 13 As it is written in the law of Moses, all this calamity has come on us; yet we have not sought the favor of the Lord our God by turning from our iniquity and giving attention to Your truth. 14 Therefore the Lord has kept the calamity in store and brought it on us; for the Lord our God is righteous with respect to all His deeds which He has done, but we have not obeyed His voice.

15 “And now, O Lord our God, who have brought Your people out of the land of Egypt with a mighty hand and have made a name for Yourself, as it is this day—we have sinned, we have been wicked. 16 O Lord, in accordance with all Your righteous acts, let now Your anger and Your wrath turn away from Your city Jerusalem, Your holy mountain; for because of our sins and the iniquities of our fathers, Jerusalem and Your people have become a reproach to all those around us. 17 So now, our God, listen to the prayer of Your servant and to his supplications, and for Your sake, O Lord, let Your face shine on Your desolate sanctuary. 18 O my God, incline Your ear and hear! Open Your eyes and see our desolations and the city which is called by Your name; for we are not presenting our supplications before You on account of any merits of our own, but on account of Your great compassion. 19 O Lord, hear! O Lord, forgive! O Lord, listen and take action! For Your own sake, O my God, do not delay, because Your city and Your people are called by Your name.”

Posted by

Brian

at

8:56 AM

4

comments

Labels: Abortion, Bible, Christian Worldview, Colombia, Former Students, Grandparenting, Lomalinda, Memoir, Teaching

Escapade @ Qasr al Yahud

Saturday, December 01, 2012

Last night at our Bible study, I was deep into recounting an

old adventure, when I realized it was exactly 40 years old, this past

week. So today, I searched the Internet

and answered questions I’ve carried with me for two-thirds of my life.

Our study had looked at Moses and the Hebrews in the desert,

as Yahweh had brought His people out of Egypt, but now intended to refine Egypt

out of His people. Then our leader

asked, “Does anybody have a desert experience they would like to share?

In Christian parlance, the term ‘desert experience’ usually

means a dry time in our lives when God works important changes in us. My story was far more literal.

|

| My future wife and my mother, seeing me off at LAX as my trip began, September, 1972. |

At Thanksgiving time, 1972, I found myself in Israel,

without much forethought. I had been

hitchhiking through Europe, with a goal of reaching Istanbul in time to mark my

ballot. I had missed voting in 1968,

when it was restricted to 21-year-olds.

Then the Twenty-Sixth Amendment gave even 18-year-olds the right to

vote, and at 22, I intended to cast my ballot for George McGovern. Sitting at the US Embassy at The Haag, I had

taken a leap in the dark, and asked for my ballot to be mailed to Istanbul.

A week later, after a visit to East Berlin and returning to

the West, on a sidewalk in Braunschweig, I had what Christians

sometimes refer to as a ‘Damascus Road Experience.’ I went into it as an agnostic, and

came out a few minutes later as a servant of Jesus Christ.

One week after that, I sat in a student-travel office in

Basel, Switzerland, trying to figure out how—once I had reach Istanbul—I could

get back into Western Europe. They

offered a cheap flight from Tel Aviv to Rome.

On the map, Israel and Turkey look close. How hard could it be to get from one to the

other?

These are all stories I will need to tell sometime, but what

is pertinent here is that during Thanksgiving week, I found myself in the

Jerusalem Youth Hostel, carrying a much-diminished cache of traveler’s checks,

but thinking I would like to take the bus down to Jericho. (I will point out that I have no photographs

of my own from this portion of my trip, because I couldn’t spare the shekels

for a roll of film. Thank you,

Wikipedia, for the use of yours.)

.jpg) |

| Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives, where I did spend some time. Photo by Alex S at en.wikipedia, from Wikimedia Commons |

A Jewish kid from San Francisco decided to join me, and so

one morning we walked to the bus station.

Had I known, right behind that station is a rocky escarpment bearing

Gordon’s Tomb, believed by many to be a more likely spot for Christ’s burial

and resurrection than the traditionally recognized Garden Tomb. However, at the time, I didn’t know, and so

didn’t walk around behind the building to take a look.

| Golgotha, the Garden Tomb, or "Gordon's Calvary," which I did not know to look at when I was at the bus station. Photo by Footballkickit at en.wikipedia, via Wikimedia Commons |

The journey through the Judean Hills doesn’t take long, and

is interesting. It follows the path on

which the Good Samaritan came to the assistance of a man who had been beaten by

robbers, and innumerable other Biblical accounts.

Once through the mountains, we could see the Dead Sea, in

the distance, though we did not make that side trip. The bus stopped once, so that a Palestinian

woman with a live chicken under each arm could disembark, though no buildings

were in sight. We probably pulled into

Jericho about 10:00 or 11:00.

There wasn’t a lot to see.

I remember one very attractive house, with a beautiful veranda of Bougainvillea. There were some citrus orchards, and date

palms. There were archaeological

diggings that one could visit for only a pittance, but I could spare not even

the pittance.

|

| Archaeological diggings at Jericho, which I did not get to see. Photo by By Abraham at pl.wikipedia, from Wikimedia Commons |

So I studied my map and realized it could not be more than

six miles to the Jordan River. At three

miles an hour, we could be there and back in time to make the last return bus to

Jerusalem, at 4:30.

| |

| Map based on http://wikimapia.org/#lat=31.8451463&lon=35.5019931&z=15&l=0&m=b |

My friend was opposed to the idea. The river was, after all, the border between

two countries that now-and-again shot at each other. I knew this.

I recognized we might not get all the way to the river, but I was going

as far as they would let me. He could

either join me, or head back to Jerusalem on his own. He decided to come.

So we set out, with the land becoming more barren as we

walked, and my friend complaining all the way.

I believe it was the same for his ancestors who accompanied Moses.

By the fifth mile, the landscape had been come steep hills

of soft sand, with some dry weeds in the gullies between them. My friend was afraid we would not be able to

get back to Jericho in time for our bus, and that we would be stuck in the

occupied West Bank over night, at the mercy of the Arabs. It was getting late.

But up ahead, there was a building. We could go just that far, I told him, and

ask for a drink of water. Then we would

go back. He agreed. As we approached the building, I noticed what

appeared to be a periscope rising from the sand, following our movements.

| Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, at Qasr al Yahud, photo by צילום:דר' אבישי טייכר, via Wikimedia Commons |

From Google Maps, I now know that the building was a Greek

Orthodox monastery, Saint John’s, and that only a third of a mile separates it

from the Jordan River and the spot traditionally believed to be where John the

Baptist baptized Jesus (though Jordan and Israel differ over whether Jesus

stepped in from the Jordanian or Israeli side).

Some traditions also name it as the spot where Joshua and the Hebrews

crossed the Jordon on their way to attack Jericho. Also, somewhere very near is the spot where

Elijah departed for heaven in a chariot of fire. At the time, none of this occurred to me, and

I recognized only that the monastery was some ethnicity of Orthodox. I also couldn’t see that just beyond the

monastery, the desert fell away rapidly to the lush bed of the Jordan.

We knocked, and the only man we saw inside got us water that

tasted of too much time in cheap plastic containers, but we were thirsty. Then the monk asked if we would like to see

the chapel. I did, though my complaining

friend did not, so I followed the monk into a small-but-dazzling room, so full

of art, icons, candled chandeliers, and mosaics that I could not take it all

in, and dared not take the time to do so.

In gratitude, I left a few coins in an offering plate, truly a widow’s

mite, but probably more than would have been the admission to the

archaeological digs.

We stepped outside to find three Israeli soldiers examining

our foot prints. They insisted that

there were three sets of prints, and wanted to know who the third person had

been. What could we say? There had never been any but the two of us.

Eventually, they accepted that, but by now it was getting

seriously late. Would they give us a

ride back to the highway so we could catch the bus? They consented, and we jumped in the back of

their pickup truck. They also had a

Jeep-type vehicle, which was good, because the truck quickly got stuck in soft

sand, and came close to rolling down the side of the hill. We jumped out.

The soldiers tried racing the wheels, but the truck simply

dug itself deeper. Then they backed the

other vehicle in front of it, and tied a thin hemp rope between the

bumpers. I tried to squelch a

laugh. Did they really think that would

hold? Apparently they did, though of

course it failed, twice, actually.

Finally, they took the other vehicle down into the gully and brought it

up behind the truck. That was

impressive. I never could have imagined

a vehicle coming up that hill in the soft sand.

But they couldn’t get the truck to budge. They decided to abandon the truck to the

Arabs and the night.

The five of us crowded into the Jeep, and they drove. But shortly the soldiers began arguing among

themselves. They stopped, took their

map, and walked to the top of a hill, making it quite obvious they were lost. Was this the army that only five years

earlier had beaten the combined armies of Islam in only six days, outnumbered

thirty-to-one? (And they would, within a

year, need only three weeks to repeat the feat.)

The soldiers dropped us off beside the highway, with about

fifteen minutes to spare before the bus came by. By my birthday, in December, I was back in

England, and by Christmas I was in California.

By the end of January, I was engaged, and by July I was married. I did not have a lot of time to ask questions

about what I had seen.

But today, I poked around on the web. Bouncing between Google maps, Google search, and Wikipedia, it was pretty easy to settle on Saint John's Monaster (Kasser, or Qasr, Al-yahud), and to realize how close I'd gotten to the Jordan River. At the time, Israel forbid access from its

bank, though I don’t know how much closer I might have gotten. We’d stayed on a dirt road, but if we had

drifted too far into the fields, we might have encountered land mines. (Americans go blithely, where even fools may

fear to tread.) Today, both countries

allow access to the baptismal site, and I know people who have visited there.

Someday, I would like to visit Israel again, and should that every happen, I will go better prepared to understand what I am seeing. But that will not take away from the adventure that Israel was the first time I was there.

In the meantime, I pray for Peace in Israel. I once rode with the Israeli army.

In the meantime, I pray for Peace in Israel. I once rode with the Israeli army.

Posted by

Brian

at

11:29 PM

5

comments

Labels: 1972, Bible, Christian Worldview, History, Israel, Memoir, Travel

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

+Hekiba+Village+.JPG)