Leonard Cohen, and thoughts related to the Yom Kippur war of 1973

Wednesday, October 11, 2023

(In mid September, 2022, I began a series commemorating the 50th anniversary of my coming-of-age trek across Europe and Israel in 1972. I posted eleven episodes before being interrupted at Thanksgiving time. This would probably come in at something like episode twenty, but I'm putting it here for other reasons which should become obvious. Technical difficulties prevented me from posting this when I first wrote it, on September 24, which was the 50th Yom Kippur since the 1973 war. It was also before the outbreak of the war now being fought.)

At a couple of minutes before 2:00, on the afternoon of Yom Kippur (October 6, in 1973, but ending at sundown this evening, September 25, 50 years later), when a coalition with troops from twelve nations launched a surprise attack upon Israel, many Jews both in Israel and elsewhere around the world were at synagogue services, observing their Day of Atonement, the most holy fast of the year. Canadian singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen, in line by birth to the Levitical priesthood, was on the Greek island of Hydra, just off the Peloponnesian coast, with a woman named Suzanne (but not the Suzanne from his song of that name) and their toddler. He was 39 and feared he was washed up as a performer. He had never served in the military, even for his native Canada, and had the reputation of being something of a pacifist. Although he had lapsed as an observant Jew, at hearing the news of war, he took the ferry to the mainland, traveling light. He did not even take his guitar.

I, a gentile, was settling into my first year of marriage. We had spent our first six weeks at a family cabin at Mt. Baldy Village, just outside Los Angeles, and now we were back in the city. I had seen Cohen in concert at UCLA, three years earlier, from a second-row seat in the very center, smack dab in front of him. While attendees were arriving to fill Royce Hall, a voice in the back began to rant wildly and Cohen came from behind the curtain. The heckler came forward and the two sat on the edge of the stage and talked quietly. Cohen settled him down and gave him a parting hug. I did not know it, but just a couple of months earlier, while touring Europe, Cohen had talked his backup musicians into a concert at a mental hospital. When a patient stood mid-concert and challenged Cohen with a question about what the singer would do for him, Cohen set aside his guitar, went into the audience, and held the man in an embrace.

Only as I researched this essay did I learn that the interrupter in Royce had been actor Dennis Hopper, a friend of Cohen’s. For a period of eight days, right then, Hopper had been married to Michelle Phillips, recently divorced from both John Phillips and the Mammas and the Papas. She would be singing backup in the second half of the show, and Hopper had talked Cohen into giving her the job. For the first half of the concert, Cohen shared the stage only with a chair, a microphone, and his guitar. He sang songs that I knew well from his two albums, most notably, “Suzanne,’ “Sisters of Mercy,” “So Long, Marianne,” and “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye.” Cohen’s genius was for quiet lullabies of detachment and desperation. Cohen had difficulty forming attachments, but he had a talent for turning goodbyes into great poetry and hypnotic music.

I'm not looking for another as I wander in my time

Walk me to the corner, our steps will always rhyme

You know my love goes with you as your love stays with me

It's just the way it changes, like the shoreline and the sea

But let's not talk of love or chains and things we can't untie

Your eyes are soft with sorrow

Hey, that's no way to say goodbye

His goodbye to Suzanne (not that Suzanne) on Hydra was more of a ‘I’m not sure what I’m doing, but I know I have to go, and I may be back.’ He got on the ferry, and then an airplane, and arrived at Lod Airport in Tel Aviv.

Eleven months previous, I too landed at Lod, with even less reason to be there. After graduating from UCLA, I bought a one-way ticket to London, thinking I would get as far as France to spend a year. Then, before I could actually use that ticket, I fell hard for the only woman I have ever loved, and to whom I am married today. Cohen and I are opposites in so many ways, yet his songs have fascinated me now for some 55 years.

I knew I was coming back Stateside in just a few months. However, while hitch-hiking through Europe, doors opened and doors closed, rides either materialized or didn’t, and instead of Paris, I visited Amsterdam, Berlin, Basel, Venice, Belgrade, and Istanbul. First in East Germany and then in the West, I encountered God in a way I could never go back upon, and in ways I don’t believe Cohen ever did. When doors opened to direct me to Israel, I was ready for it. I arrived at Lod airport on an El Al flight from Istanbul. At both ends of the flight, passengers faced the strictest security I have ever seen, even after 9/11. In that November, 1972, only six months had passed since members of the Japanese Red Army pulled machine guns from their luggage, killing 26 and injuring 80.

Cohen had been to Jerusalem in April, at the end of his 1972 European tour. Once on stage, he’d become flustered when the crowd applauded after the first few words of “Like a Bird on a Wire.”

Like a bird on the wire,

like a drunk in a midnight choir

I have tried in my way to be free.

He stopped singing and explained why he could not go on with the concert, “…it says in the Kabbalah that unless Adam and Eve face each other, God does not sit on his throne. And somehow, the male and female part of me refuse to encounter one another tonight, and God does not sit on his throne. And this is a terrible thing to happen in Jerusalem.” (https://www.israellycool.com/.../when-leonard-cohen.../) Cohen then walked off, followed by the band. At that point, the audience took up spontaneous versions of well-known songs in Hebrew. Back stage, Cohen shaved while the promoters and band tried to coax him back on stage. In his guitar case, he found an old package of LSD, which he split up among them, later describing the shared acid as “like the Eucharist.” It was Cohen’s special talent to use sacred imagery to describe the profane. After this ‘priestly’ duty, Cohen returned to the stage, crying, to listen to the crowd sing, and add a song of his own.

In Jerusalem, I located an acquaintance from UCLA, named Ilene. The next day, she snuck me onto a field trip with her Palestinian Archeology class. In the role of academics, we hopscotched north along the Jordan River, to stops in Galilee and catacombs near Haifa, listening to lectures. Then Ilene and I hitchhiked for a weekend in Safed, an artist’s colony and the highest city in Israel. Under the Ottoman rulers, Safed had been the study-center of Kabbalah. Alongside Israeli soldiers, we waited for rides at hitching points. The soldiers then put in a good word for us with any drivers who stopped. We rode along the border of the Golan Heights, chatting with our armed escorts. In Safed, we watched a continuous pattern of Israeli Air Force planes patrolling the Lebanese border, only about ten miles away.

In Tel Aviv, Cohen thought he would volunteer for work on a kibbutz, but visited cafés that he remembered from the disastrous tour of 20 months earlier. There, musicians recognized him and invited him to help entertain troops in the Sinai Desert, where the war was going very badly. They found him a guitar.

Actually, the war was going badly everywhere. The simultaneous attacks from Egypt into the Sinai and from Syria into the Golan Heights had caught an overconfident and relaxed Israel during a holiday. Observant Jews were between the first and second of the three main portions of the liturgy, and non-observant Jews were indulging themselves in secular pleasures.

Cohen would have been in this second group. Although raised in a Montreal synagogue founded by his rabbi grandfather, and deeply infused by its rhythms and language, Leonard Cohen was faith-curious, but living the life of a secular man. Israeli journalist Matti Friedman, author of WHO BY FIRE: LEONARD COHEN IN THE SINAI, describes Cohen’s public image as “a poet of cigarettes and sex and quiet human desperation, who’d dismissed the Jewish community that raised him as a vessel of empty ritual, who despised violence and thought little of states…” (p. 5). Yet much later, when Cohen was residing at a Zen Buddhist monastery, just two miles upstream from my family’s cabin at Mt. Baldy, he would tell an interviewer, “…I was never looking for a new religion. I have a very good religion, which is called Judaism. I have no interest in acquiring another religion.” (p. 41)

It intrigues me that Cohen, and an impressive list of other secular Jews, including Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Randy Newman, and Carly Simon, provided my generation with its musical score and lyrics, the Psalms of our secular experience.

Cohen knew well that he had been born in the bloodline of priests—Kohanim in Hebrew—running through his grandfather, then through 3,000 years of fathers and sons to the generation of Zadok, chief priest at the time of Solomon’s Temple. Finally it sound its Levitical source in Aaron, the brother of Moses. Cohen struggled with that. A new acquaintance in Tel Aviv sized him up quickly, “You must decide whether you are a lecher or a priest.” (p. 166). In notes he assembled just after the war, perhaps for a novel he never produced, Cohen recounts, “The interior voice said, you will only sing again if you give up lechery. Choose.” (p. 48). In the Temple, one whole branch of the priests were singers. Cohen was at a point in life where he doubted even that hereditary gift.

What Cohen could not have known, at least until he was living at the Zen Monastery, was that DNA studies in the late 1990s concluded that the genetic code bore out the historicity of this Kohanim tradition. Researchers have identified a pattern of genetic markers that is as much as ten times more common among Cohens than for non-Kohanim-Jews. That holds true among both Ashkenazi and Sephardic populations, and even for Lemba tribesmen in Zimbabwe and South Africa, who maintain a tradition of Jewishness.

Out in the Sinai Desert, at one end of the father-to-son chain of Kohanim, Moses recorded God’s declaration that only men from this one family could service the Tabernacle. Among their duties would be calling the people away from their daily tasks, often ministering during the worship with singing and musical instruments. Now, at the other end of the chain, Leonard Cohen, much though he might want to escape the priesthood, was heading into the Sinai to minister in music to the troops.

The Sinai was bathed in blood. The small troop of musicians would drive until they saw a cluster of soldiers, stop, and sing a few songs. Sometimes these soldiers were just arriving from hot battle, with minutes-old images of flying ordinance and falling comrades. Many were not sure who this singer was, nor could they understand the English of the songs he sang. He spoke no Hebrew. Few understood that here was a musician who had sung in 1970 before for a crowd of 600,000 on the Isle of Wight. Most were more excited to see the Israeli singers that they recognized. Cohen sang standing in a tight circle of soldiers, or sitting in the sand, or on the scoop of a bulldozer. One photograph shows him standing in front of General Ariel Sharon, who is talking to a well-known Israeli singer. Later, Sharon did not remember that Cohen had been there. (p. 141)

counter-offensive across the Suez into Egypt. At one point, Cohen helped carry stretchers with wounded soldiers from helicopters to a makeshift hospital. His memoire records that as they moved through territory that had seen recent battle, he recoiled against the sight of bodies littering the sand, but felt relief when he learned the dead were Egyptians, not Jews. Then he felt guilt for feeling that relief. Those had been some mothers’ sons. There was no LSD to cushion what he was seeing, only soldiers’ rations and quick naps on the sand. In between performances he worked out a new song, though the recorded version is gentler in places than the verses he sang in the desert.

I asked my father

I said, father change my name

The one I'm using now it's covered up

With fear and filth and cowardice and shame…

He said, I locked you in this body

I meant it as a kind of trial

You can use it for a weapon

Or to make some woman smile...

Yes and lover, lover, lover, lover, lover,

lover, lover come back to me

Yes and lover, lover, lover, lover, lover,

lover, lover come back to me

Then let me start again, I cried

I want a face that's fair this time

I want a spirit that is calm…

Yes and lover, lover, lover, lover, lover,

lover, lover come back to me

Yes and lover, lover, lover, lover, lover,

lover, lover come back to me

Of the three liturgical high points of the Yom Kippur commemoration—due to its solemnity, not to be confused with a celebration—the first, a thousand-year-old prayer called Unetaneh Tokef, had been recited before the coordinated attacks. It begins, “Let us relate the power of this day’s holiness.” It speaks of God’s judgements, the insignificance of man, and projects the idea that this Day of Atonement seals everyone’s fate for the coming year:

How many will pass on and how many be created,

Who will live and who will die,

Who will reach the end of their days and who will not,

Who by wind and who by fire,

Who by the sword and who by wild beast,

Who by famine and who by thirst… (p. 16)

This prayer formed the inspiration for Cohen’s 1974 song, ‘Who by Fire.’

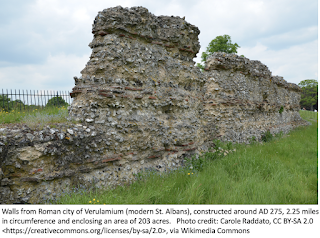

During the second high point, all the male Cohens in the congregation stand around the gathering to recite a blessing that was left as a vestige after the destruction of the Second Temple, by the Romans, in 70 AD. “May God bless you and guard you. May God shine His face upon you and be gracious to you. May God lift up His face to you and grant you peace.” (p. 17)

The third and final highpoint, reached at the very end of the 24-hour fast, when everyone is tired, is a reading of the Book of Jonah, the most complex history ever presented in 48 sentences. At the beginning of 2022, on my short list of New Year’s resolutions, I wrote that I wanted to better understand Jonah. Eighteen months later, I think I am finally getting it, although perhaps I’m not taking the same message that all Yom Kippur worshippers are receiving.

Jonah, a prophet of God, is told to take a message to the people of Nineveh, not only pagans, but as wicked and blood-thirsty a city as ever existed. Jonah hops a boat going the opposite direction. He knows that he cannot escape from God, but perhaps he can escape from his job description. In a storm, he finds himself in the hands of pagans more righteous than he, but God uses him to demonstrate to those pagans His own awesome power. Then Jonah is swallowed by a fish, and surrenders himself to God’s will. The fish spits him up on the shore, and Jonah goes to preach in Nineveh. I have seen speculation that after three days stewing in a fish’s stomach juices, Jonah may have arrived in Nineveh looking like God’s demonstration project. The Ninevites repent, and God spares them from the judgement that He had pronounced. Jonah goes to sulk on a hilltop, where God provides a vine for shade and then a worm to kill the vine. Jonah is angry at God, both for His mercy on the wicked Ninevites and for taking away the protective shade, and God challenges him that he has no right or reason to stand in judgement on the Creator.

Why should Jonah’s memoire be read as the culminating activity on the Day of Atonement? In a very real sense, Jonah is Everyman, and we are all in need of atonement. We have all, together, and each, individually attempted to run from God and the job descriptions He has given us. We have all and each of us attempted to cast judgement on God for both the unrighteous who He has blessed and the righteous He has apparently overlooked. Even honest atheists, if they examine their hearts, will likely discover that their disbelief in God is rooted in those judgements.

But for Israel—and ratchet it up a notch for the Cohens—the job description is even more direct. Beginning with Abraham, God’s chosen people, like Jonah, were chosen to be God’s demonstration project. In this allegory, the rest of us are Ninevites.

The temptation for the chosen is to run as Jonah did, or to pass the job description off on others. Fiddler on the Roof’s Tevye, addressing God, says, “I know, I know. We are Your chosen people. But, once in a while, can't You choose someone else?”

God very clearly sets out the stakes in this demonstration. By the time we get to Deuteronomy, chapters 27-30, Moses has completed his 40 years leading the Hebrews around in the Sinai. He gives his final instructions—rules against theft, mistreatment of the vulnerable, and lechery. Then, before turning them over to Joshua’s leadership and sending them across the Jordan, Moses tells the leaders that once they are in Israel, they are to put half the people on Mount Gerizim. There, they will shout a list of blessings that will come from obedience to God. Facing them, the other half will stand on nearby Mount Ebal, to shout curses that will follow disobedience. The script acknowledges that it’s for demonstration purposes. Concerning the blessings: “Then all the peoples on earth will see that you are called by the name of the LORD… “ (28:10a) Then later, concerning the curses: “The LORD will cause you to be defeated before your enemies. You will come at them from one direction but flee from them in seven, and you will become a thing of horror to all the kingdoms on earth.” (28:25). And again: “You will become a thing of horror, a byword and an object of ridicule among all the peoples where the LORD will drive you.” (28:37)

The curses require a long chapter, remarkably foretelling the actual experience of the Jewish Diaspora: “Then the LORD will scatter you among all nations, from one end of the earth to the other…” (28:64) “Among those nations you will find no repose, no resting place for the sole of your foot. There the LORD will give you an anxious mind, eyes weary with longing, and a despairing heart. You will live in constant suspense, filled with dread both night and day, never sure of your life.” (28:65-66)

However, Chapter 30 speaks of a restoration. Many of the families that were taken away to Babylon in the exile never got back to Israel. Cohen’s ancestors became Polish and Lithuanian Ashkenazim. Other families became the Sephardic population of Iberia. Yet over the course of 2,500 years they never lost their identity or the pull of the land. “Then the LORD your God will restore your fortunes and have compassion on you and gather you again from all the nations where he scattered you. Even if you have been banished to the most distant land under the heavens, from there the LORD your God will gather you and bring you back.” (30:3-4)

That pull was so strong, that when a secular and lecherous Canadian Cohen, while fleeing his priestly calling, heard that Israel was under attack, his response was, “I’m not sure what I’m doing, but I know I have to go, and I may be back.”

Labels: 1972, Bible, Books, Christian Worldview, Famous People, History, Israel, Memoir, Milestones, Travel, UCLA, Yom Kippur

Thanksgiving 2022

Thursday, November 24, 2022

(We interrupt the previously scheduled episode recapping my 1972 Coming-of-Age Jaunt through Europe, to interject this Thanksgiving message.)

I am thankful, three weeks before my 73rd birthday, that most of my deadlines these days are self-imposed and freely adjusted. Had I been able to maintain my original plan, this week would have had readers with me in Jerusalem, where I celebrated my 1972 Thanksgiving meal with a jar of peanut butter and the loaf of bread I hoped to stretch for a few more days. Instead, the recap falls short by six weeks and eleven nations. I was still in England, and still thinking I would spend most of my sojourn in France. I anticipated upgrading my high school French and working on my novel. I certainly had no inkling of getting as far as Israel. I had, however, just committed to visiting a new friend in Switzerland.

I give thanks for my God-bestowed but only-recently-acknowledged ADHD. Even as—at this stage in life—unfinished projects challenge me in space and time, the fascinating twists and turns of my distractibility refuse to let me become bored. I am rich in both hobbies and relationships. All by itself, my whimsey in spiders has brought me friendly correspondents on six of the seven continents. My early teaching career allowed me to teach groups of junior high students, and in some cases, my later career brought me their children and grandchildren. Members of each group now show-up richly on my FB friends list. As God supplied me with diverse teaching venues, I once had a class of Cacua-speaking adults from the remote jungles of Colombia. They needed the basics of government and economics to help them pass their (Spanish-language) primary-school equivalency exams. We taught the class tri-lingually. Later, in China, I had three weeks with high school and college students who hoped to improve their English. Over the years, God gave me experiences with both public and Christian school students in California. In the middle, for a decade, I taught a tightly-knit cadre of students in Colombia. Some of those children I had the privilege of shepherding from fifth grade through twelfth, and I’m able to correspond with them now as adults. For all this I am thankful.

I am thankful for the families God has given me, both the family of my birth, and the family I began 50 years ago (next July) by marrying Vicki. In July, I camped with the cousins among whom I grew up. We who could remember our wonderful grandparents and great-grandmother could now see each other’s grandchildren. This week, Vicki and I have three of our five children, with their spouses, and seven of our fourteen grandchildren. My step-counter tells me that in the five days since the grandkids arrived, my daily walking stats double over the average from the previous six weeks. Few gratifications in life can match watching grandchildren grow and their parents negotiating the challenges. The oldest two boys have their voices changing. The younger ones still want to cuddle with Papa and have stories read. I also thank God for the amazing technology that allows me to teleport to Brazil to help homeschool my grandsons there, and then zoom over to England to keep current on the antics of my British grands.

My life puts flesh to the end-time description given by God to Daniel, “Many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall increase.” (Dan. 12:4, ESV). Living now, two-and-a-half millennia after God instructed Daniel to “shut up the words and seal the book, until the time of the end,” I am grateful to have a storehouse of ‘to-and-fro’ memories from visits to twenty-some countries. I also carry more information through my pocket phone than Ben Franklin or Thomas Jefferson could access had they owned every book then in print. I am thankful for capabilities unavailable to any previous generation. I am also grateful for the Scriptures that provide a solid place to stand as floodwaters shift the sand from all around us.

As a child born just at the end of two World Wars, I have lived through a Cold War and times of increasingly dangerous proxy wars. I am thankful that both I and my children have been spared the call to arms. Amidst ‘wars and rumors of war,’ I am thankful that, in my call to overseas service, I could carry literacy rather than kill-or-be-killed armaments. I could spread the Word of Life rather than the Kiss of Death. I am thankful to be living in a pocket of peace, the likes of which so many in our world are unable to enjoy. I am not facing a winter without heating, nor the threat of incoming missiles. I have done nothing to deserve these blessings that I enjoy, just as many of the people without them have done nothing to deserve their absence. Even in Colombia, which was struggling with a civil war within our earshot, I could say, as did David, “In peace I will lie down and sleep, for you alone, LORD, make me dwell in safety.” (Psalm 4:8). For this I am thankful.

(A conversation, just now, with my Brazilian son-in-law reminds me how thankful I am to be familiar with the tastes of both the peaches, apricots, and plums that won’t grow in the tropics, and the tree-ripened mangoes, papayas, and bananas that only show up in North American grocery stores with a pittance of their sweetness and flavor. I have tasted avocadoes, sweet and creamy as only the tropics can produce them, but have temperate-zone persimmons in the back yard as I write this.)

I am thankful that though riches and fame were never high on my list of ambitions, God’s plan for my life has delivered for me a modest level of each. I enjoy a nice house, a satisfactory pension, and a yard big enough to entertain my horticultural curiosities. Although—as late as 2016—I entertained no ambition to run for elective office, in 2018, I finished ahead of the Libertarian in my race for Congress, and in 2020, an amazing 42,015 voters marked their presidential ballots for me. I am thankful for each one of you. That total exceeds even the popular votes for George Washington (39,624 in 1788-89, and 28,300 in 1792) and for John Adams (35,726 in 1796). I am thankful that both Washington and Adams performed so well in the strenuous times with which they were faced—as have generations of patriots since—and that my family and I can enjoy the benefits thereof. I pray that those benefits will continue.

Even as God blessed me in ways I never sought, He has also gratified the desires I did entertain. I wanted to leave the world a better place for my having been here. Now, I can look at five grown children who are each contributing to the betterment of mankind. I can look at three generations of students whose lives I have touched. I can see riders lined up to utilize a bus system for which God put me in the right place at the right time to help get started. I can look back at teenagers I encouraged in the 1980s—coming from the pre-literate, indigenous peoples of Colombia—students who went on to graduate from prestigious universities, and who now supervise educational systems they have built from the ground up, on land to which their people now hold legal title. I hear of hundreds now worshipping Jesus among people-groups that had none fourty or fifty years ago. Oh, the marvels I have witnessed! Thank you, LORD!

On this Thanksgiving Day, 2022, I pray that each of my readers will enjoy a time of family and good food. I pray for God’s peace among those, worldwide, who currently feel the weight of man’s free will, expressed as it so often is, as man’s inhumanity to man. Come quickly, Lord Jesus.

Labels: 1972, 2020 Elections, California, China, Christian Worldview, Colombia, Europe, Facebook, Fatherhood, Former Students, Garden, Grandparenting, History, Israel, Lomalinda, Memoir, Milestones, Spiders, Teaching, Travel

Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #3

Friday, September 23, 2022

I found a free map of London and walked the city for two days. I soon learned that the three things I needed in order to learn a new city were a map, a couple of days, and walking.

Travel teaches us much about a foreign place. By comparing and contrasting, we also get fresh eyes to better understand what we consider home. In 2022, looking back 50 years, I am struck by how much my travels have taught me about myself, as well. The passage of time has a similar effect. I’ve been thinking as I write this about my cousin Lance, who would have celebrated his 23rd birthday on the day I flew from Los Angeles to London, if only had he not drowned in a scuba accident when we were both 17. At 17, Lance never got a chance to learn just who he was. I am also comparing my trip 50 years ago with the current trip of a friend who is posting each day from Greece. I am learning a great deal about Greece, but more-so, although I have considered her as family and admired her for 40 years, I am also gaining new insights into who she is, and comparing her meticulously planned trip with my trip, which had almost no planning at all.

My plan was to go over there and have a look around.

I wouldn’t be traveling in total ignorance, because I had been visiting England vicariously since meeting Benjamin Franklin in a children’s book at the age of eight. Franklin first visited London to study the art of printing. He lived there again, 1757-1762 and 1764-1775, as the representative of the Pennsylvania colony. Increasingly during those years he also became the primary representative for all the British colonies on the Atlantic seaboard. I could imagine myself arriving in London much as Franklin had arrived in Philadelphia, a run-away, walking the city with bread stuffed in his pockets.

I did walk past the house marked as Franklin’s home. It’s a mere ten-minute walk from the Parliament building. He rented rooms in that building for almost 16 years. In Franklin (along with Jefferson, who much preferred France) I’d had my first hero, my first tastes of travel, and—I realize now—not an imaginary friend, but a friend from another era, and a soul mate. I could not have told you for another 25 years anything about Myers-Briggs personality typology, but somehow, my shared characteristics with Franklin (ENTP and the often-concurrent ADHD) grabbed me, and in the process hooked me on history, biography, geography, and a layman’s fascination with anthropology, zoology, botany, linguistics, meteorology, and all the other interests that Franklin (and INTP Jefferson) found to interest them.

By the time I landed in London, I had read biographies of Churchill, Gladstone, Henry VIII, Victoria, Elizabeth I, Drake, Darwin, Florence Nightingale, Admiral Nelson, Newton, Faraday, Cromwell, Richard the Lion Hearted, and Raleigh; and read works by Shakespeare, Austin, Dickens, Tolkien, Lewis, and Orwell. I had also studied my English genealogy, including the Rev. Stephen Bachilor, a Puritan divine who brought four grandsons and my mother’s line to Boston, in 1632. After some scandal (there is evidence that his fourth wife formed the model for Hester Prynnes, in Hawthorne’s ‘The Scarlet Letter’), Bachilor returned to London for his final years. On a later trip I would do a search for his grave.

From Earl’s Court to Buckingham Palace is a three-mile walk, or slightly farther if one takes a route along the Themes. I looked in on whatever I could enter without a fee, which included several hours in the Victoria and Albert Museum and an hour-or-so in the balcony listening to a debate in the House of Lords over a bill to install culverts beside roads somewhere. Several walks through the Hyde and St. James Parks gave me a baseline to judge change in the city during my four return trips. (On a Sunday in 2000, it seemed like most of the women in Hyde Park were dressed in black hijabs and niqabs.) I remember crossing a Themes bridge one evening after lights were on, and coming upon the statue of a young woman, and thinking very much about Vicki. On future trips to London, I have ventured farther upriver and down, but on this trip, there was plenty to see in the center of the city.

My London walk included locating offices of the Youth Hostel Association, where £20 bought me membership, a guide book, and a map of all the Youth Hostels in Europe. I was on my way.

Labels: 1972, Books, Europe, Famous People, History, Immigration, Linguistics, Memoir, Milestones, Travel

Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #2

Saturday, September 17, 2022

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

I had an address for a bed and breakfast in Earl’s Court, a mere 32 miles away. I had walked that far in a day previously so even after I realized my mistake, I was not concerned. I had hiked the high Sierras. I ran run cross country in high school and my first year of college. I’d run a marathon in Mexico. I once got my high school class to challenge the class just ahead of us to a contest to see which class could rack up the most total laps on a Saturday, and personally tallied 33 miles, so I set out on a beautiful sunny morning to walk to Earl’s Court. I probably walked past dozens of bed and breakfasts that would have served me well, but a friend had given me the address of the place he’d stayed in Earl’s Court.

First time travelers may be struck by the fact that a foreign country appears in the same colors as at home, but somehow looks different. I was pondering that when a car stopped and a young man offered me a ride. I gladly accepted, and obeyed his instructions to stow my rucksack in the boot. Do you know that the British drive on the wrong side of the road? They also seat the driver on the wrong side of the car. I had read about it, but now I saw this peculiarity verified.

When my benefactor learned that this was my first day in England, he decided to divert and show me some local Roman ruins. We had a most congenial time, and then he let me out to continue on my way. The countryside gradually gave way to industrial areas, and then brownstone residential areas, and then I was in Earl’s Court. I had successfully flown across an ocean, walked most of 32 miles, gotten some exercise (though not much to eat), met a native, seen some Roman ruins, and located a target address. I decided I ought to recount my safety and my successes in letters to Vicki and my parents.

Of course, I had no return address to offer them other than the bed and breakfast in Earl’s Court, and it would be two weeks for my letters to get to California and receive answers back (Note to those who grew up in the age of email and texting: Letters were a thing that allowed Neanderthals to communicate over long distances, albeit very slowly). On the plus side, those two weeks would allow me time to visit Ireland before continuing to France, where I would hunker down with my novel and the French language. I still entertained that objective.

A few thoughts from 50 years later:

After yesterday’s episode, I messaged with a high school friend who did her travel with the army, as a nurse, and though she did not go to Vietnam, the topic came up in our discussion. For my generation, it often will. For my cohort, our post-high-school years were either spent in Vietnam or trying to stay out of Vietnam, or maybe protesting in the streets over Vietnam.

Like many of my peers, I was conflicted about Vietnam. I loved my country and wanted to defend it, but questions nagged me about whether in Vietnam we were the good guys or the bad guys. I started college three days after high school, not because I wanted to avoid the draft (Note to those who grew up in the era of an all-volunteer army: It used to be that when the letter from the draft board arrived, you reported for military duty). In 1968, the best way to stay free of the draft was to stay in school. Although I did want to avoid the draft, my primary motivation for college was excitement about college. However, those first weeks, I buddied around with a friend who really wasn’t that excited about school. Toby dropped out, got drafted, and died standing in the boot camp breakfast line. A recruit standing behind him dropped his rifle.

After watching the sun come up over the English countryside, I landed at Luton International Airport before 7:00 AM, and committed my first rookie error within minutes. I carried no British pounds, but had $600 in US Traveler’s Checks. (Note to those who grew up in the age of ATMs: These used to be a thing, allowing traveling Neanderthals to go to a bank and obtain cash.) I supposed a better exchange rate at banks farther from the airport, and as it was still too early for banking, I decided to walk as far as I could before banks opened. It skipped my mind that banks observe no hours at all on Sundays.

The spring I was finishing up at community college and getting ready to transfer to UCLA, the employment office connected me with a middle aged veteran who needed a man Friday. Pat suffered from emphysema, due to an accident in the Air Force. He knew he was dying, and wanted to do so in Europe. My job would be to carry his oxygen tank, and then accompany his body home at the end. He would pay all of my expenses and a nice salary. Most importantly for me, it would be my longed-for trip overseas. I look back on that episode as the supreme test of my transition to adulthood. Going with Pat would mean I would have to cancel my plans for UCLA. Pat told me Sen. Cranston owed him some favors and could fix me up with the draft board. Although I didn’t want to go to Vietnam, I also didn’t want some politician pulling strings for me. I drove Pat to Cranston’s office, but the Senator had been called away that day. Pat was expecting a big check from the government, but I began to wonder if it was actually coming. Pat liked to brag about the friends he looked forward to seeing, but from his description, some of them impressed me as a little shady. He also talked about the girls he would be able to get me, and how they could move in with us. That wasn’t the kind of girlfriend I wanted. After investing five or six months in Pat’s dream, and as much as I wanted to see Europe, I realized that I wanted to be my own boss when I traveled. I told Pat I was going to UCLA. To have gone with Pat then would have traded away everything of value that I have today.

I remained timid and indecisive about the war. I took part in a few demonstrations, and wavered over the question of what to do if drafted. I could not imagine killing another human being. Maybe I would go in as a medic. Maybe I would go to Canada. Dying for my country was one thing, but what if our side was actually the bad guys? That would be worse than dying in the boot camp breakfast line.

One more friendship stands out: I had written a 500 page—typed, double spaced—murder mystery (Note to those who learned word processing at a computer key board: Word-working was once done at a manual instrument that left one’s fingers raw and swollen at the end of the writing day). I had alternated 12-hour writing days with days carting Pat around. UCLA had a novel writing contest that first quarter and my 500 pages lost to a Vietnam vet’s 30-page opening chapter. Brian Jones took his $5,000 prize, went home and beat up his wife. The prize went for her hospital costs and the divorce. Over the next two years that I had to get to know him, I watched the Man Who Had Everything slowly fall apart.

We did not understand PTSD in those days, nor PITS (Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress), a concept first described by Psychologist and Sociologist Rachel MacNair. As I heard MacNair present at a conference in 2019, and then driving the carpool back to our shared AirB&B, she put into words exactly what I sensed had happened to Brian Jones. Brian had been the All-American everything: football quarterback, Student Body President, going steady with the head cheer-leader. Then he had done the All-American thing to do in 1966; he joined the Marines. When I asked about his experience in Vietnam, he could only shrug and say, “I killed a lot of Gooks.” There is PTSD trauma that soldiers experience when bullets are flying and friends all around them are dying, but PITS kicks in when someone raised with high moral values must face that they have become a murderer. Within a few months of my return from Europe, Brian Jones drove a van full of marijuana over a cliff, while running from police.

I believe I have seen PITS twice more. For a while I was visiting and corresponding with an inmate on Death Row in San Quentin Prison. He had been convicted as a serial killer. Independent research brought me an account of a childhood murder-dismemberment (of his mother) in which he had been forced to participate. Every one of his murders had been a reenactment of that event.

And then, in helping a friend clean up after a tenant, I found the letter-to-herself of a woman whose life had spiraled down after an abortion. Her agony came out in one haunting line, “This is not who I am!”

In 1972, as I left for Europe, the United States was struggling with a similar disconnect. “This is not who we are!”

Labels: 1972, Abortion, Aviation, Europe, Friday 10:03, History, Memoir, Milestones, The Writing Life, Travel, UCLA

Coming of Age, 1972: Episode #1

Friday, September 16, 2022

Fifty years ago, today, I boarded a flight in Los Angeles and flew to Luton, just north of London, UK. Thus began the great coming-of-age adventure of my life. My mother and my then girlfriend (Vicki, who has now been my wife for 49 years) saw me off at the airport. In flight, I remember the Rocky Mountains covered with a layer of golden-yellow Aspen trees, ice chunks floating in Hudson Bay, an hour in a duty-free shop beside a snow-cleared runway in Iceland, and the first rays of daylight as we took off from Edinburgh. I was 22, and—unlike today—I had been able to work my way through UCLA with no debts, and graduate with $1,000 in the bank.

I did not walk in the graduation ceremonies. Skipping those expenses gave me another hundred dollars for my voyage. Instead, I walked from my last final exam to a student travel agency and bought my one-way ticket to Europe. The other choice had been Japan, which interested me more, but five years of French would serve me better than my three quarters of Japanese. It was my plan to sojourn for a year in Paris. I would work on making my French useful, and write on the novel from which I had already shown Vicki portions over a year earlier. My last quarter at UCLA had been exhausting. During registration, a counselor pointed out that I had accrued 207 units, and once I went over 208 without graduating, I would not be allowed to register for another quarter. I had transferred in from community college with more than the usual totals, and then decided to add a kinesiology minor and creative writing classes to my history major. I also, wanting to explore what eventually became my career, took the ‘Education of the Mexican-American Child’ class in which I met Vicki. The gist of it was, to complete all my graduation requirements, I needed to take and pass 28 units my final quarter. I may have set the all-time UCLA record for most units to earn a BA. As I returned to campus after buying my ticket, I looked out on the sea of peers who were practicing for the ceremony. Was there even one person I needed to say 'goodbye' to? Vicki came to mind. Our almost-two-year relationship had been friendly, but not romantic, and I did not see much chance that I could find her in the crowd. I did see her roommate, who promised she would pass along my goodbye. My main activity for the summer would be two volunteer sessions as a camp counselor, one with teen diabetics and the second for kids who came largely from Los Angeles Chinatown, where I had been tutoring English during my time at UCLA. One preparatory task for that was interviewing the families for each camper. One of those families spoke only Spanish. I had not yet begun the Spanish which would later serve as my almost-competent second language, so I called Vicki and asked if she would translate for me. On a Saturday morning I picked her up and we drove to Chinatown, but the family was not at home. I knew there was an Asian-American culture fair going on that weekend at nearby Echo Park, so we went there to kill some time. The family still wasn’t home, so we drove to USC, where Vicki would be taking classes for a teaching credential. We did a lot of talking. By the time I got her home in the late afternoon (unbeknownst to me, she had a date she needed to get ready for), I had begun to rethink our relationship. We had a wild summer. By the time Vicki and my Mom dropped me off at LAX, I was much less sure that I wanted to be gone for the full year. As we parted, I whispered, “I’ll be home for Christmas.”Labels: Aviation, Europe, Friday 10:03, Language Acquisition, Light at the End of the Tunnel, Memoir, Milestones, Teaching, The Writing Life, Travel, UCLA

Golden Yellow Aspen Trees: Looking back 50 Years and down 35,000 Feet

Friday, September 09, 2022

Fifty years ago, this week, and looking down at the Rocky Mountains from an altitude of 35,000 feet, the memory I retrieve is hundreds of miles of Aspin trees, in their September golden-yellow magnificence. Glued to the window two hours into my coming-of-age trip, I guessed first that the amazing sight might be blooming goldenrod. Then I realized the blaze of color was not flowers, but autumn leaves. Growing up in Los Angeles, I’d not had much experience with fall colors. Sadly, my useless little camera had no way to catch the grandeur nor the color of the Quaking Aspen.

After the goodbyes in L.A., my views of the western United States seemed mostly parched and drab. After the Aspen in Colorado, my next strong memory is chunks of ice floating in Hudson Bay, then snow piled beside the runway in Iceland. Finally, I saw the first hints of dawn while taking off for the last leg from Glasgow. Travel stimulates memories like no other activity I know. I cannot remember what I had for breakfast yesterday, but I can reach back 50 years and recount my day-by-day events, conversations, and impressions for the three months of my travels. Then, I can contrast what I actually did with what I’d expected to do, and see how those experiences determined the rest of my life. It had been my original plan to take a brief look at London and then go to France. I would find a room, work on my novel, and finally learn the language that had eluded me through five years of high school and college coursework. Instead, my ADHD and ENTP curiosity would kick in. I would visit Wales, Ireland, Belgium, Netherlands, the two Germanies, Switzerland, Italy, Yugoslavia, Turkey, Israel. I’d spend just the briefest couple of days in France, leaving me with French I still can’t speak, and I am now 50 years closer to finishing my novel. Dwarfing all that, though, I left home an agnostic—although intrigued—but came home a firm believer in Jesus Christ. Between now and Christmas, regular readers of my feed can expect to see me reliving the highlights from those three months, though I have several off-topic essays in process as well (see ‘ADHD and ENTP,’ above). Oh, and I’m working again on my novel. I hope many of you stop by.Labels: 1972, Europe, Friday 10:03, Light at the End of the Tunnel, Memoir, Milestones, Plants and Flowers, The Writing Life, Travel

Rosh Hashanah and My New Year's Resolutions

Tuesday, December 14, 2021

On this December 14th, and just one day shy of my birthday, I’m looking back at my 2021 New Year’s resolutions and the goals I set out in January, and which I hope to recalibrate for the year ahead. For starters, twelve months ago I resolved to reduce the amount of stuff that encumbered me. There I’ve had partial success. I did empty out one storage shed, though I had hoped to complete a second one. A visitor might not notice the improvements in my garage and office, but I do. Health-wise, I had hoped to drop 30 pounds in 2021, in preparation to lose another 30 in 2022. For this year, I only have 25 of the 30 to go, but I will keep trying. I intended to get out and walk more. After previous annual averages of 1.6, 1.5 and 1.4 daily miles, I’m at 2.0 for 2021. It helped that I discovered podcasts and a headset, but I had hoped for closer to five. I will keep working at it. I had hoped to finish my novel. Oh, well. I will pursue that in 2022, if the Lord tarries. My most successful efforts came in my reading and Bible study. I wanted to read once through the entire Bible and then spend extra time in Jonah. On that, I am on track for success. I’ve been on-and-off in Jonah throughout the year, and in the daily readings from The One Year Bible, Jonah shows up, well…for today, December 14. Jonah interests me because I think that those of us who have God’s Word—and who can see the signs of coming judgment—are called to carry the warning while there is time for the world (and individuals in it) to seek God’s mercy. Jonah understood the task, but tried to flee. God, however, would not let him get away. There are powerful lessons to be learned in that. My study of Jonah was helped by the mid-year discovery of the Bible Project Podcast, and their weekly teaching. They spent one whole month on how to read the Bible, and used Jonah as their sample text. I don’t believe I have missed any of their programs since March or April. Over the summer, I put several of their episodes on repeat, listening to individual programs four and five times while I worked in my yard. I hope to continue that in the next year, and recommend them to my readers. Forty-nine Octobers ago, I discovered that the greatest victory in life came from surrendering one’s life to Christ. During these 49 years, I have managed complete reads through the Bible five times. One summer I used the vacation to go straight through, Genesis to Revelation. Other years I’ve used various reading plans, including The One Year Bible. Last year I was about 60% successful. This year, I’m on track to finish the 365 fifteen-minute portions on December 31. Each day comes with a couple of chapters from the laws, histories, and prophets of the Hebrew authors; a chapter or so from the New Testament; a section from Psalms; and two or three verses from Proverbs.

I find great value in juxtaposing passages that may have been written a thousand years or more apart. The Bible deals with the biggest of all possible pictures, and needs to be seen in its continuity. Themes, conflicts, and puzzles introduced in Genesis find climax, answers and denouement in Revelation. Although a cursory understanding of Jesus—sufficient even for someone to find faith—can come from just a few New Testament verses, a deeper appreciation comes from long and careful study that includes the early writings from Hebrew. Conversely, the multiple mysteries presented in the Old Testament find their solutions in the New. We see God set up a standard to which no generation nor any single individual can manage to achieve, and yet God promises forgiveness, acceptance, and that there will be a group who enjoy unlimited and unending fellowship with Him. As well, God identifies the Hebrew people as His choice among all the peoples of the world, and yet He promises to bless all those other peoples through the Hebrews. Readers follow the developing promise of a coming someone special, but that someone looks sometimes human and sometimes divine. He is sometimes presented as gentle and self-sacrificing, even unto death; but then, in passages that seem to be chronologically later, he is revealed as the ultimate conquering king. Without Jesus, so many of the stories in the Hebrew histories seem random and contradictory. What’s with Abraham sacrificing Isaac? How do we explain Joseph tossed into the pit by the brothers who are later held up as Patriarchs? How do we interpret the bronze serpent in the desert? We’re given strange dreams, recorded with the idea that someday they would make sense, and given festivals for which God exacts very precise details. We plod through failure after failure by the supposed heroes of the story. We see prophetic voices announcing the most horrendous judgments, and yet those prophets end their individual writings on optimistic looks into the future. All this comes within a pattern of God accomplishing seemingly contradictory goals in ways that could not have been humanly imagined, yet each makes perfect sense after it is completed. God is master over the mutually exclusive. Common to both sections of scripture are the promises of separation and restoration. The Hebrew people, true to promises in Deuteronomy 28, have spent much of their history blown around like dust in the wind, spread among every other nation on earth. One year before my birth they again became a nation with a physical homeland under their own government. The Messiah also went away with the promise to come back. When His disciples asked Him when that would be, He gave them a parable about a fig tree. They had, in fact, seen Him curse a fig tree, just a day or two before His crucifixion, and the tree had died. In the Bible, the fig tree is often used as a symbol of the Hebrew nation in physical possession of the land, as opposed to grape vines and olive trees, which held reference to spiritual and religious aspects for the Jews. Jesus tells His disciples, “Now learn the parable from the fig tree: as soon as its branch has become tender and sprouts its leaves, you know that summer is near; so you too, when you see all these things, recognize that He is near, right at the door. Truly I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things take place. (Matthew 24:32-34, see also Mark 13 and Luke 12). The children who in 1948 watched news reels of the Israeli flag hoisted for the first time over Jerusalem are all older than me, and I will be 72 tomorrow. The clock is ticking on the cohort just ahead of me. Jesus warns us that “about that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but the Father alone.” (Matt. 24:36) Then He draws a parallel with the generation lost in the flood during Noah’s time, and follows with two stories of people who were not paying attention, nor were they ready at the arrival of a calamity or an important person that they should have expected. He finishes with a command, “Therefore be on the alert, for you do not know which day your Lord is coming.” (Matt. 24:42) Throughout history, various ones who have tried to calculate the day and the time of Christ’s return have ended up sadly embarrassed. In 1843 and 1844, in the heat of the Second Great Awakening, followers of William Miller went through a succession of anticipated dates. They gave away properties, dressed in white, sat on rooftops waiting, and ultimately were let down by the Great Disappointment. In the 1950s and ‘60s, as Mao Zedong’s Communists murdered perhaps one million believers, or about one out of every three Chinese Christians, we can perhaps forgive those Christ followers for expecting that Jesus would soon return. The same might be expected among Christians in Afghanistan today, or in Nigeria, or North Korea. Yet Christ absolutely tells us to be watching and alert. We are to be cognizant of famines, earthquakes, and events in the weather, ‘wars and rumors of wars,’ and events in the heavens. His return would come after the Good News (Gospel) had been preached to the whole world, a process that I was privileged to observe in a small part during my time in Colombia. One after another, Bible translation teams delivered that prerequisite into remote languages that had never previously had it. The Bible also gives us patterns to internalize as New Testament events fulfill Old Testament prototypes. Jesus—whom John the Baptist calls ‘The Lamb of God’ (i.e., the Passover sacrifice, John 1:29)—at the Last Supper interpreted His broken body and shed blood as the bread and wine of the traditional Passover and Feast of Unleavened Bread. His death on the cross, at the very moment that priests in the nearby Temple were sacrificing lambs for the nation, and on the same mountainside where Abraham had been prepared to sacrifice his son Isaac—fulfilled such passages as Genesis 22:8, Isaiah 53, and Exodus 12. Even as the Jewish leaders tried to avoid crucifying Jesus during the feast, Jesus exerted control, assuring that His sacrifice would occur at the correct prophetic moment. Fifty days later, on the Feast of Pentecost (Weeks, or First Fruits), the Holy Spirit fell on the crowd of worshippers, giving birth to the church, the ‘first fruits’ of Christ’s harvest. The next prophetic event, corresponding as well to the next feast on the Jewish calendar—the one I will be watching for this year, and the next, and the next, until it happens—is Christ’s return, or Second Coming. The feast is called variously Yom Teruah, Rosh Hashanah, the Feast of Trumpets (or shouting), or sometimes, ‘the feast of which no man knows the day or the hour.’ This last is because on the first day of the seventh month, the announcing shofar is blown only when those watching the heavens actually see the first sliver of the new moon. That could be delayed by cloudy weather. Observant Jews set aside all work and spend the day in quiet and prayer. The Apostle Paul describes the event I am waiting for this way, “For the Lord Himself will descend from heaven with a shout, with the voice of the archangel and with the trumpet of God, and the dead in Christ will rise first. Then we who are alive, who remain, will be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air, and so we will always be with the Lord.” (1 Thessalonians 4:16-17) This year, one of my resolutions is to be watching the heavens during Rosh Hashanah (September 25-27, 2022). If necessary, I will do the same in 2023 (Sept 15-17), and 2024 (Oct. 2-4). It’s possible that in this coming year, I will be joined by many who have no interest in Jesus. Those observers will be captivated by NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART). In this first attempt at kinetic impactor technology, NASA hopes to ram an asteroid out of its set path. Their target is Didymos B, a smaller asteroid, or moonlet, that orbits a larger asteroid, Didymos A. Launched November 23, 2021 from California, DART is set to intercept the Didymos duo 6.8 million miles away from Earth, on September 26, 2022. We will all be watching on the same time September days. ‘Didymus’ means ‘twin,’ and with a slightly different spelling, it was a nickname for Thomas, the disciple who was not present when Christ first appeared to the other disciples. Upon hearing their report, he said, “Unless I see in His hands the imprint of the nails, and put my finger into the place of the nails, and put my hand into His side, I will not believe.” Eight days later, when Christ again appeared to them, He turned to Thomas and said, “Place your finger here, and see My hands; and take your hand and put it into My side; and do not continue in disbelief, but be a believer.” Thomas answered and said to Him, “My Lord and my God!” Jesus said to him, “Because you have seen Me, have you now believed? Blessed are they who did not see, and yet believed.” (John 20:27-29) My 2022 New Year’s resolutions will include more attention to losing some weight and getting out to walk more. I will work on my novel, the garage, and that last shed. I intend to read again through the whole Bible, but this time, maybe I will set a schedule to finish before Rosh Hashanah. And now, I need to go read Jonah, and passages from Revelation 5, Psalm 133, and Proverbs 29.Labels: Bible, China, Christian Worldview, Colombia, Friday 10:03, History, Israel, Memoir, Milestones, The Writing Life

Forty-Eight Generations and a Birth Announcement

Saturday, February 12, 2011

Somewhere in the deep recesses of history, God told man to be fruitful and multiply: to fill the earth.

Somewhere in the deep recesses of history, God told man to be fruitful and multiply: to fill the earth.

In the early 6th Century, when Bishop (later, Saint) Arnulf of Metz (582–640) stepped into verifiable history, claiming a possibly-mythical ancestry of Roman senators and Merovingian princesses, the population of Europe stood at perhaps 25 million. Arnulf begat Ansegisel (born c. 602), who begat Pippin the Middle, Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia, who begat Charles Martel, who saved Christendom from the Moors at Tours, in 732. Charles begat Pepin the Short, who reigned (752-68) as King of the Franks.

Pepin begat Charlemagne, King of the Franks from 768, and Emperor of the Romans, from 800 to his death. For his reforms, Charlemagne has been called the Father of Europe, but he was also, biologically, ancestor to every royal dynasty that later inhabited the continent. It is estimated that more than half the population of Europe—maybe fifteen million people—lived in his realms. He personally sired 20 children, by eight women, but conservatively, if we suppose that his progeny only doubled in each successive generation, had there been no intermarriage, his living descendents today would be triple the current population of earth.

Charlemagne begat Louis the Pious (778 – 840), King of the Franks and Holy Roman Emperor, whose daughter Gisela (820 – 874) was likely married to Henry of Franconia and bore Ingeltrude, whose a son Berengar ruled as lord of Rennes until both his land and his daughter were captured by the Viking chieftain Rollo (Old Norse, Hrólfr, c. 870 – c. 932). Poppa converted her husband to Christianity (though Viking habits die hard), and their descendents were known as the Dukes of Normandy: William I Longsword (893-942) begat Richard I the Fearless (933-996), who begat Richard II the Good (970-1026), who begat Richard III (997-1027), who begat Robert I, called variously “the Magnificent” or “the Devil” (1000-1035), who begat William II the Bastard (c. 1028-1087), who shed that moniker at the Battle of Hastings, in 1066, becoming William I the Conqueror, King of the English.

England, with perhaps a million souls at the conquest, grew to as many as seven million within three centuries. A warming trend brought longer growing seasons. Better ploughs and the horse collar allowed more land to be farmed. The rise of powerful kingdoms brought relative stability.

William begat Henry I (c. 1068-1135), whose daughter Matilda (1102-1167) was briefly Empress of the Holy Roman Empire. When her father died, she attempted to rule England in her own right, but was more successful in passing the throne to her son Henry II Plantagenet (1133-1189).

Henry acknowledged paternity of William Longespee (1176-1226), whose daughter Ida (1210-1269) bore Beatrice de Beauchamp (1242-1285), who bore Maud Fitz Thomas (1265- 1329), who bore Ada de Botetourt (c. 1288-1349), who bore Maud de St Philibert (1327-1360). Even while the Black Plague was ravaging Europe, claiming 40% of the population of Germany, 50% of Provence, and 70% of Tuscany, this Maud bore Maud Trussell (1340-1369), who bore Maud Matilda Hastang (1358-c. 1409), each woman married to a knight. Maud and her husband, Sir Ralph (1355-1410) brought forth the first Sir Humphrey Stafford (1384-1419), whose death in France just weeks after the victory at Rouen may have been due to wounds in the battle, but not before he sired a second Sir Humphrey (1400-1450), who sired a third (1426-1486), who sired a fourth (1429-1486), who sired a fifth (1497-1540), whose daughter Eleanor (c. 1545-1608) bore Stafford Barlowe (c. 1570-1638), “a Gentleman of Lutterworth.”

Stafford’s daughter Audrey (1603-1676) first bore a son, Christopher Almy (1632-1713), and then both generations migrated to America, settling in Rhode Island. He begat Elizabeth Almy (1663-1712), who bore Rebecca Morris (1697-1749), who married John Chamberlain, and moved to New Jersey. It is believed the Chamberlains owned slaves. Their son Noah (1760-1840) served in the Revolutionary War.

Noah begat John C. Chamberlain (1812-1866), who begat Samuel L. Chamberlain (1842-1914), who fought with an Ohio regiment in the Civil War, and then walked out on a wife and daughter, Anna Margaret Chamberlain (1875-1956), who I remember meeting once, when I was very small. Anna hailed from Scotch ancestry. The population of Europe doubled during the 18th Century, and did so again in the 19th. At that time, 70 million people came to America, both to the United States, and to places like Brazil.

Anna Chamberlain married Thomas Boyer Reef Kelley and bore Ruth Ella Kelley (1899-1974). They tried to make a go of it on the Dakota prairie, but gave up and moved to be near the shipyards in Washington. Ruth married Howard Vincent Carroll (b. New York, 1898). He was of recent Irish and German extraction, refugees of the Potato Famine. Today, 6.2 million Irish live in Ireland, and 80 million live somewhere else. Howard left Ruth with two sons, including Donald, who has been everything a son could want in a father. Donald begat Brian, who teaches school and blogs on Saturdays. Brian begat Matthew, who has been everything a father could want in a son, and Matthew—already with two wonderful sons—begat Eliezer Carroll, who was born yesterday, in Goiania, Goiás, Brazil.

Welcome, Eliezer, to the family. We are saints and devils, counts and no-counts. There are not quite 7 billion of us. Help take care of the place, be fruitful, and live long.

Photo by his father

Thank-yous to Sally Carroll, Devin Carroll, and Wikipedia for contributing information to these thoughts.

Labels: Brazil, Europe, Famous People, Fatherhood, Grandparenting, History, Immigration, Milestones

A Civil Fred Korematsu Day, to You and Yours

Saturday, January 29, 2011

Tomorrow will be Fred Korematsu Day, as will January 30th in all future years, declared so by Governor Schwarzenegger and the unanimous desire of both houses of the California Legislature. Parallel days in Oregon or Washington might honor Minoru Yasui and Gordon Hirabayashi. In my own mind, it will be Jiro Morita Day, and by extension—like a Rosa Parks Day or a César Chavez Day—it will be a time to reflect on how citizens in a supposedly civil society can respond at those moments when civility is in jeopardy.

While I was growing up, each of my parents spoke of the pain and confusion they felt in 1942 when their Nisei classmates were sent away to government “Relocation Camps.” Later, while I was taking a year of Japanese language at Pasadena City College, the school offered “Sociology of the Asian in America.” The course might qualify among the ethnic studies courses that have just been outlawed by the state of Arizona, but I look back upon it as one of the most fruitful classes I ever took. Three hours one night a week, with a 20 minute break, I quickly began spending those twenty minutes—and the walk to the parking lot after class—with Jiro Morita. At 80, he told me he was taking the class “to stay young.”

I spent every possible moment asking about his long life.

In early 1942, when the United States government was preparing to lock up the entire Japanese community on the west coast, the Japanese themselves worked through intense debate over how to respond. Poet Amy Uyematsu, Mr. Morita’s granddaughter, writes,

Grandpa was good at persuading the others

after the official evacuation orders.

Detained at Tulare Assembly Center,

he was the voice of reason among his angry friends,

raising everyone’s spirits

when he started the morning exercise class.

(From “Desert Camouflage,” in Stone Bow Prayer)

Most of the issei (1st generation immigrants) and nisei (2nd generation/US citizens) decided that obedience to the government’s order would offer their best long-term hope for full integration into American society. Three American-born young men, however, decided to test their 14th Amendment rights and protections. Korematsu, Hirabayashi, and Yasui performed that most-American of exercises: they took it to court.

Korematsu (1919 – 2005), born in Oakland, first tried plastic surgery and a name change to evade the order for Japanese to report for relocation. When that failed, he agreed to let his arrest be used as a test case. Korematsu remained at the Topaz, Utah, internment camp while Korematsu v. United States worked its way to the Supreme Court. They decided against him, 6-3.

Although Korematsu was an unskilled laborer, both Hirabayashi (b. 1918, in Seattle) and Yasui (1916-1986, of Hood River) had earned bachelors degrees from their state universities. Yasui even held a law degree and the rank of second lieutenant in the U.S. Army's Infantry Reserve. The relocation order was preceded by curfews, which each man intentionally violated before surrendering to authorities. Eventually the Supreme Court linked the two cases and rendered a unanimous decision: The government had the authority to order detention and relocation of even U.S. citizens under its war powers. Korematsu’s conviction was not overturned until 1983, Yasui’s until 1986, and Hirabayashi’s until 1987.

Source

In the early 1970’s, I had a brief, chance meeting with Gordon Hirabayashi. During my two years at UCLA, I studied additional Japanese language and a year each of Japanese and Chinese history. I also volunteered as an ESL tutor at Castelar Elementary School (L.A. Chinatown), and as a summer counselor for an Asian session of Unicamp. This took me often into the Asian American Study Center, where Elsie Osajima, Mr. Morita’s daughter, was an administrative assistant. Once, when I entered Mrs. Osajima’s office on some errand, I found several people chatting with Mr. Hirabayashi. It was very like a similar meeting, during the same months, and no more than 500 yards apart, with former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Earl Warren. In each case, I knew it was a rare privilege to connect with an important moment in history, and yet the situation didn’t allow for me to ask questions. On the spur of the moment, I couldn’t even think of any.

However, the two meetings provide an interesting juxtaposition. Earl Warren, as Attorney General of California, was the driving force behind convincing President Roosevelt of the necessity for removing the Japanese from their homes and communities. The same Warren Court (1954-1969) that did so much to advance civil rights in so many other areas also could have been the court to reverse Korematsu, Hirabayashi, and Yasui. It didn’t. What my parents identified immediately as wrong when their high school chums were hauled away in 1942, the federal courts only caught up with in the 1980’s. Then, California recognition had to wait until 2011.

If there is a lesson in Earl Warren’s life, it is that for any community, prejudice is easiest to see from outside the area, or outside the era. Warren could see the prejudice against African Americans in the South, yet at the same time, he was either blind to, or unwilling to face prejudice against the Japanese in California. This brings us back to Arizona, today, and the efforts to redefine citizenship. Fred Korematsu looked back on his own case and pursued justice an a reversal of the court's decision, not for his own sake, but so that the United States could be counted on to give the 14th Amendment guarantees to every person ever born or naturalized in the United States, and in whichever state they might reside.

May it ever be so.

As I prepared this post, the miracle of Google allowed me to connect with Amy Uyematsu and Elsie Osajima. I intend soon to write more about Jiro Morita. He was an amazing man.

In the meantime, enjoy a civil Fred Korematsu Day. Pick an injustice, and ponder how to alleviate it.

http://www.amerasiajournal.org/blog/?p=1840

http://www.amerasiajournal.org/blog/?p=1840Additional Resources:

Korematsu v. United StatesHirabayashi v. United States

Yasui v. United States

Ex Parte Endo

In this PBS video, Mr. Korematsu tells his own story.

This book targets readers from 3rd to 6th grades.

This book targets grades 7 through 10. Although it appears to be out of print, used copies may be available. Perhaps, now that California has an annual Fred Korematsu Day, it will be reprinted.

Gordon Hirabayashi - On the Day of Remembrance: A Statement of Conscience

Gordon Hirabayashi - On the Day of Remembrance: A Statement of ConscienceIn this nearly-two-hour from 2000, Gordon Hirabayashi discusses the Japanese Evacuation and its importance to history.

Disclosure of Material Connection: The Amazon links above are “affiliate links.” This means if someone clicks on the link and purchases the item, I will receive a commission. This has never happened to me as of today, and would only be a pittance if it did. I have no financial arrangement concerning any of the other materials I have linked with. I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.”

Labels: Anecdotes, Bilingualism, California, Famous People, History, Immigration, Japan, Memoir, Milestones, UCLA

DC-3 Nostalgia Follow-Up

Monday, January 24, 2011

Last month’s Capers tribute to the DC-3 became part of a conversation, both here and on Facebook, that included several of my former students and a couple of students who graduated from Lomalinda before my time.

Garth Harms obtained this picture from photographer Jeff Evans, who spent a couple of months in Colombia just before I got there. That dates the picture to late ’83 or early ’84.

Photo by Jeff Evans

It’s authentic, right down to the left-wheel and rear-wheel ruts where the plane pivoted to put its passenger door facing the covered waiting area. The entire community was here to receive my family when we stepped off the plane the first time, and in turn, we joined the crowd for countless welcomings and goodbyes. Departures had a ritual: after final hugs, the doors closed but the waving continued. Then the engines would rev (first one side, then the other) and well wishers would jump on motor cycles for a race to the last hill at the end of the runway, for final salutes as the gooney bird lifted off. This airplane was central to so many emotional moments that just looking at the picture—all these years later—touches a nerve.

One educational advantage that students in Lomalinda enjoyed was an unusual opportunity for work experience during high school. Kirk Garreans tells me he had the privilege of working alongside the DC-3 crew. Through his connections, he also came up with the fact that DC-3s continue to be active in the relief efforts in Haiti. Ponder that a moment: the youngest DC-3s are 65 years old, and still play a role in work-a-day aviation. Amazing.

Kirk also traced “our” DC-3 to its current owners, Dynamic Aviation, of Bridgewater, Virginia. The firm supplies “special-mission aviation solutions,” with over 150 aircraft doing commercial charter, fire management, sterile insect application, airborne data acquisition and other tasks. Before writing my first post, I was 90% certain I’d found the airplane, but Kirk’s information locked it. Dynamic Aviation restored the craft (N47E) to its original, 1943, Air Force paint job and insignia, and renamed it “Miss Virginia.” Here it is:

Finally, Kirk reported that Miss Virginia was part of the twenty-six plane, 75th Anniversary Fly-In to Oshkosh. Several nice videos are posted on You-Tube. Here is one:

A tip of the wings to all who participated in this conversation.

(My earlier post is here.)

Labels: Aviation, Colombia, Facebook, Former Students, History, Lomalinda, Memoir, Milestones, Photography, Product Reviews, Travel

Happy Birthday, DC-3

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

In the rush of Christmas, I’m a little late with this post. I had hoped to have it ready for December 17th, when one old friend turned 75 and another turned 108.

On December 17, 1935, at Santa Monica, California, test pilots tried out the first DC-3. Exactly 32 years earlier, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, Orville and Wilber Wright piloted their Wright Flier 1 to what is generally considered the first sustained flight by a self-propelled and pilot-controlled aircraft.

I’m not a pilot, but I enjoy being a passenger. I love both the arriving in some exotic place and—under most conditions—the process of getting there. Maps fascinate me, as does the world they represent. (Ask the two generations of students to whom I have assigned map learning.) Having the earth stretched out beneath me is like enjoying the map in its purest form. I have pressed my nose to the window of multiple crossings of the Atlantic, the Pacific, and the Caribbean, and on flights that puddle-jumped across four continents.